A Slap of Reality: Peasant Culture According to Superstudio

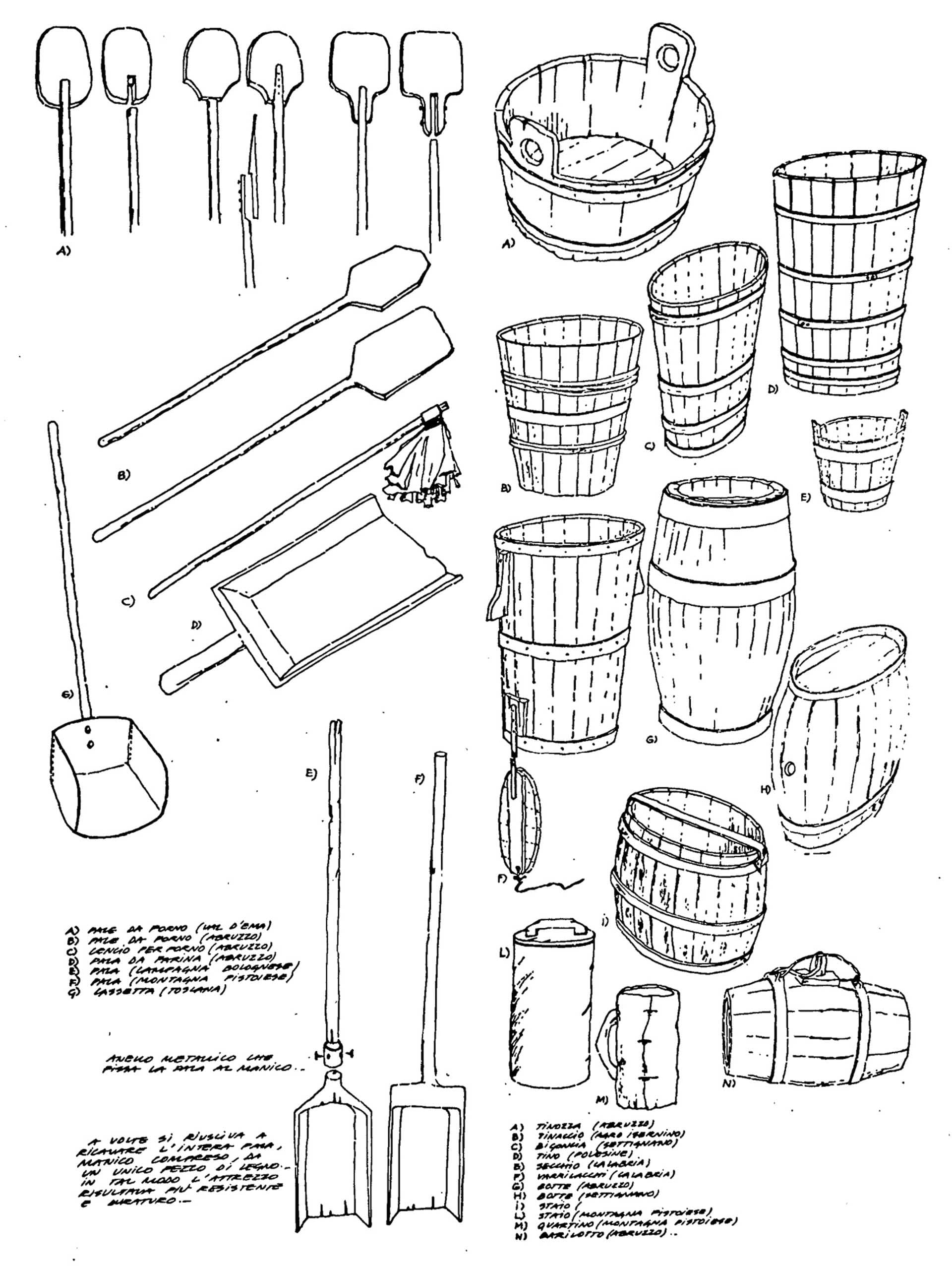

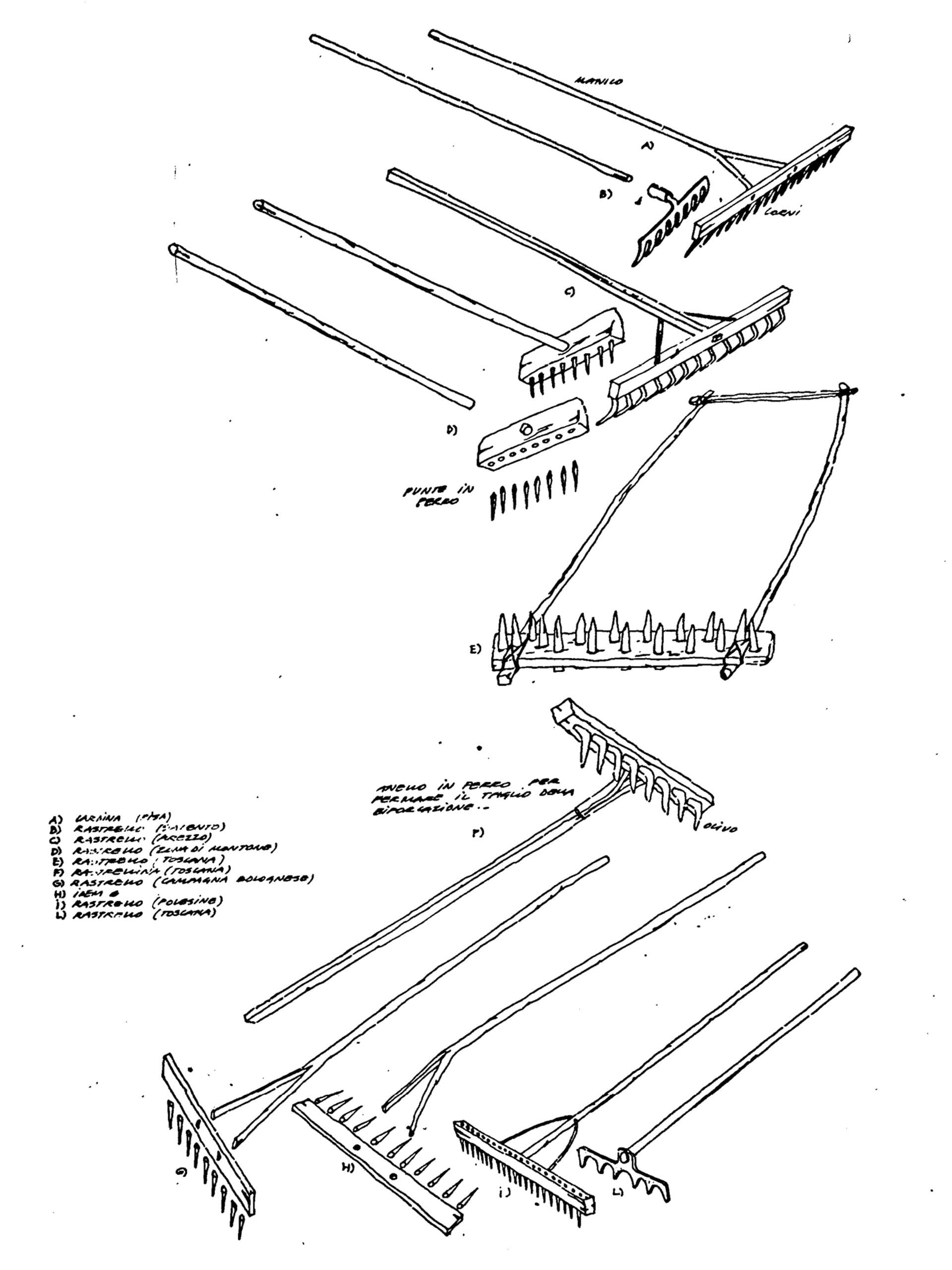

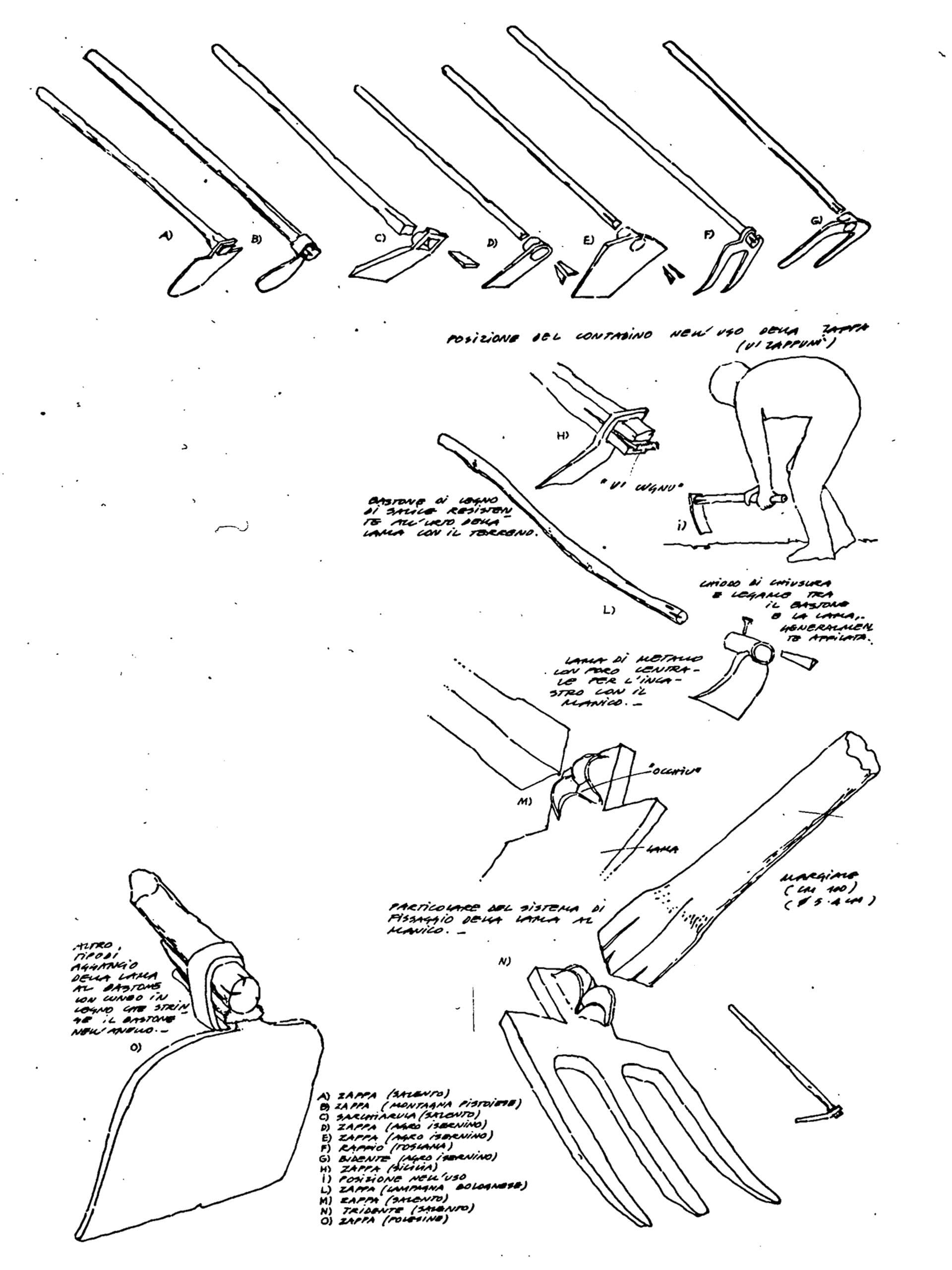

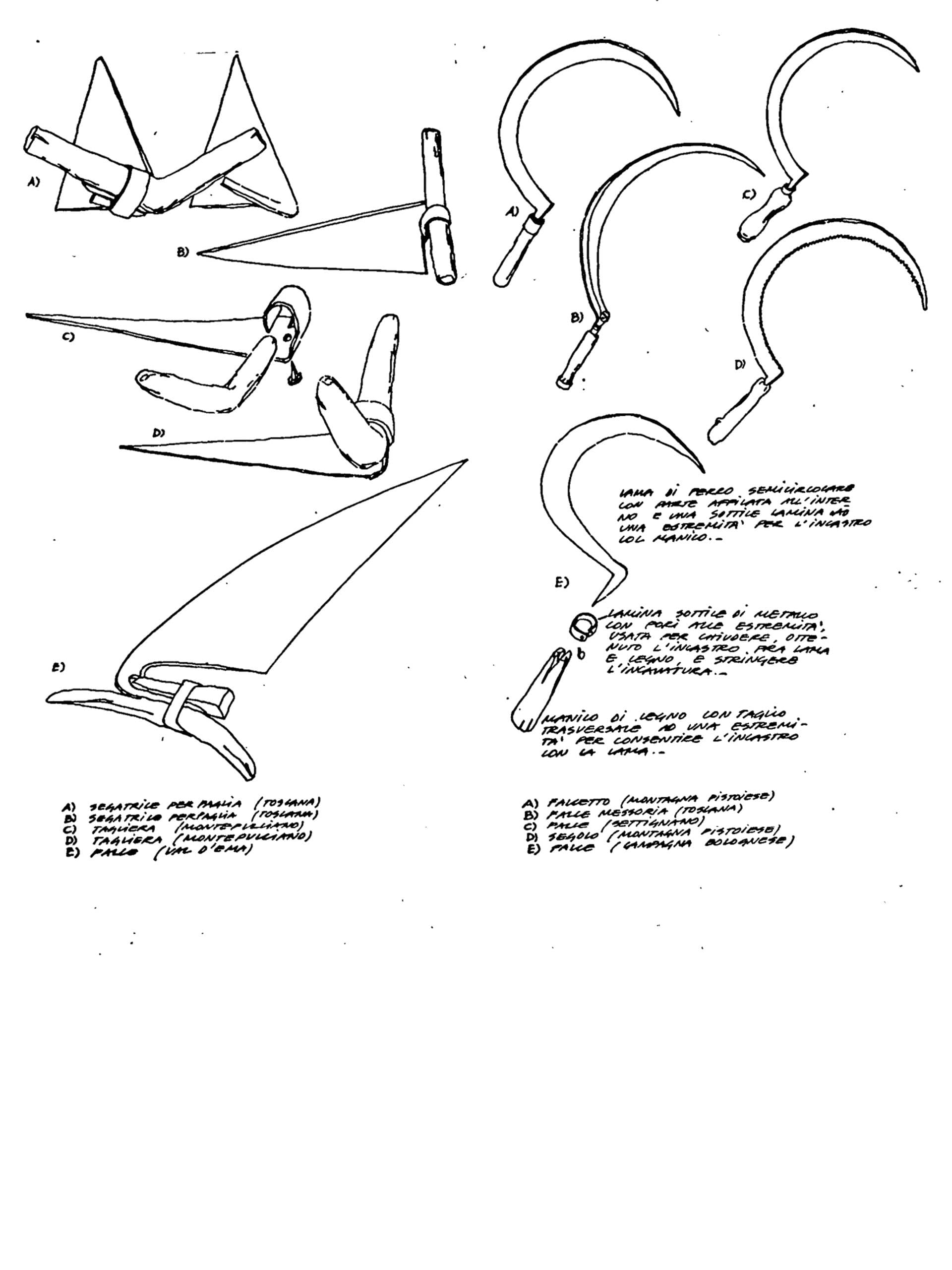

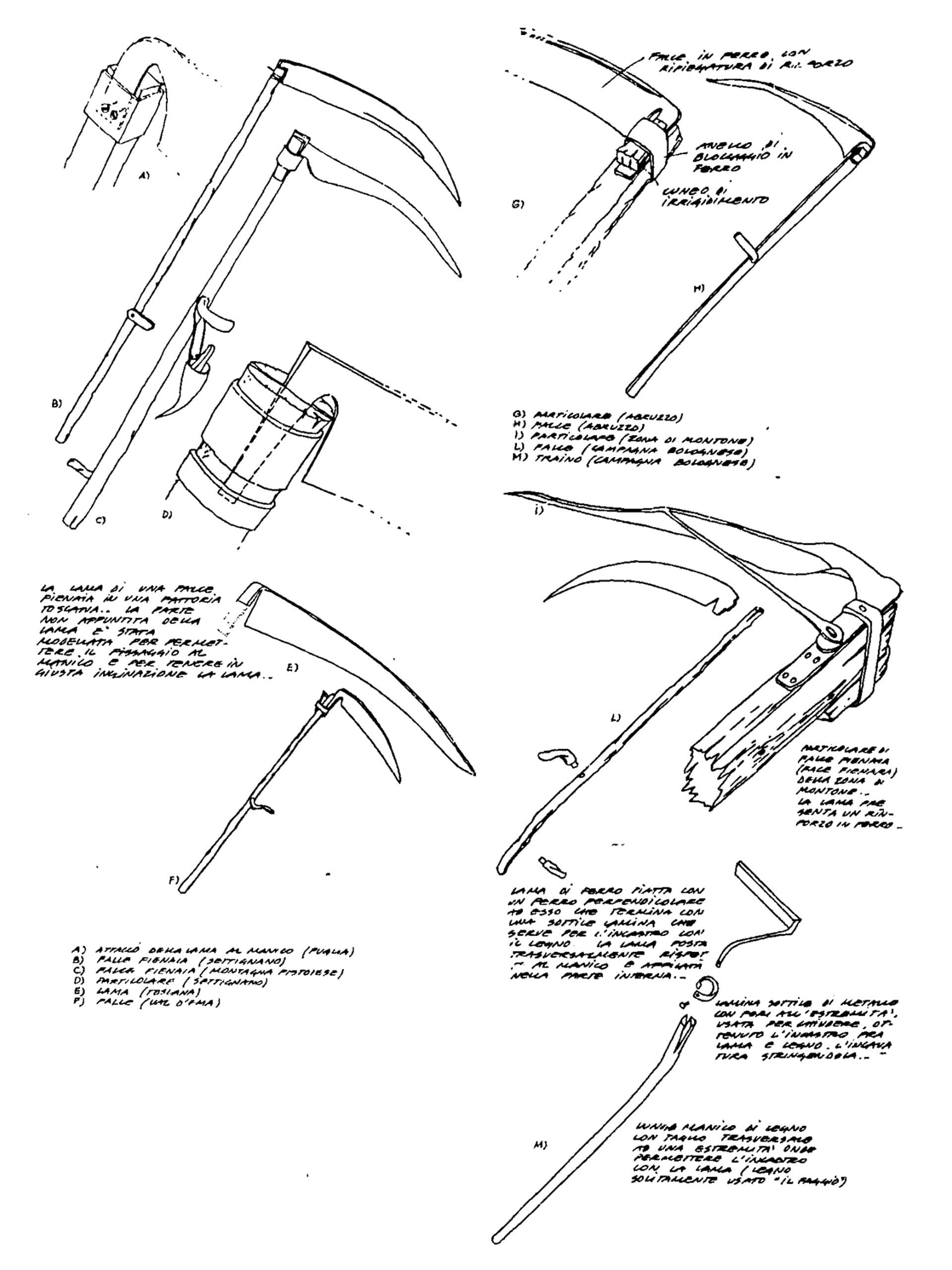

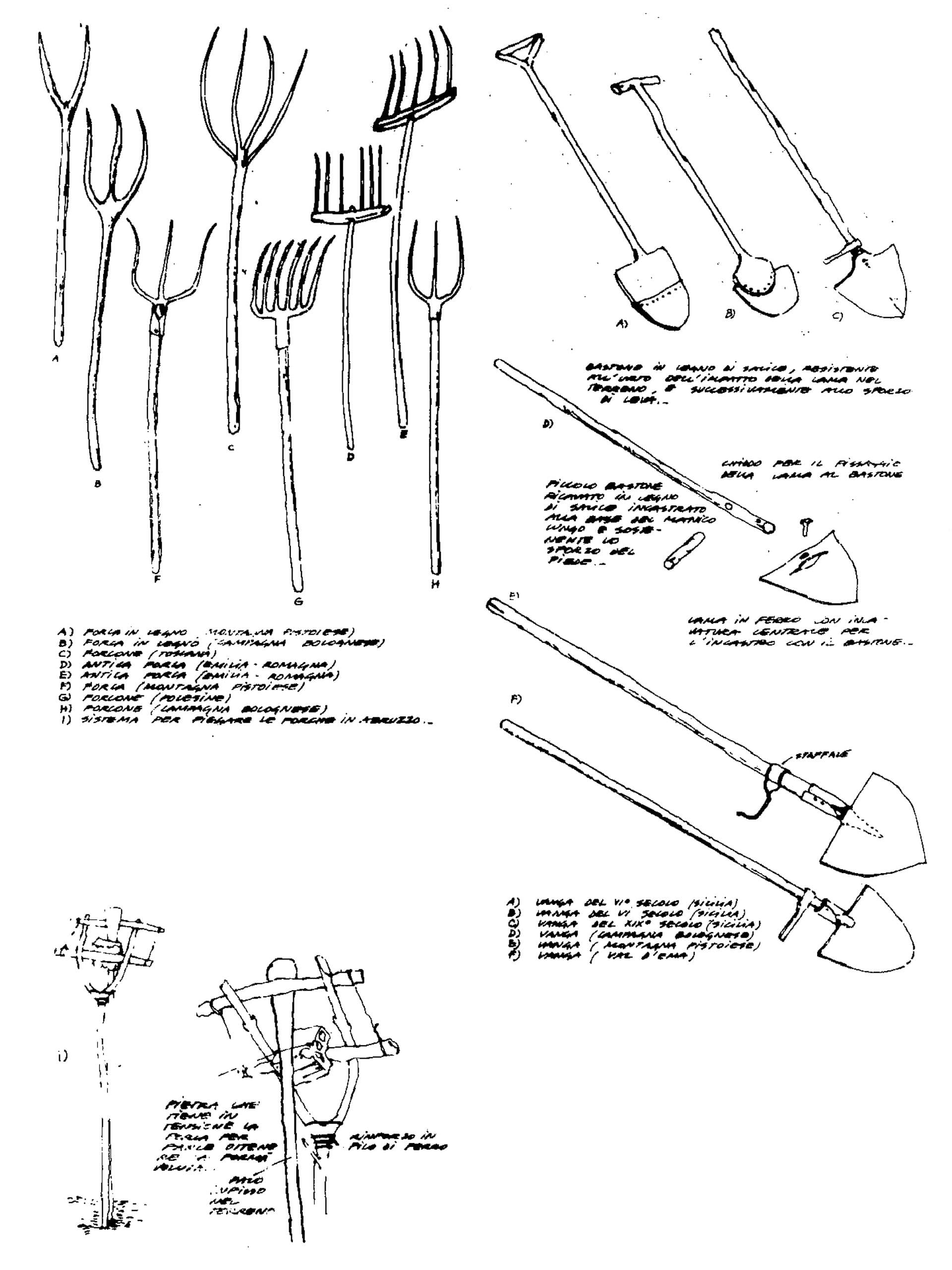

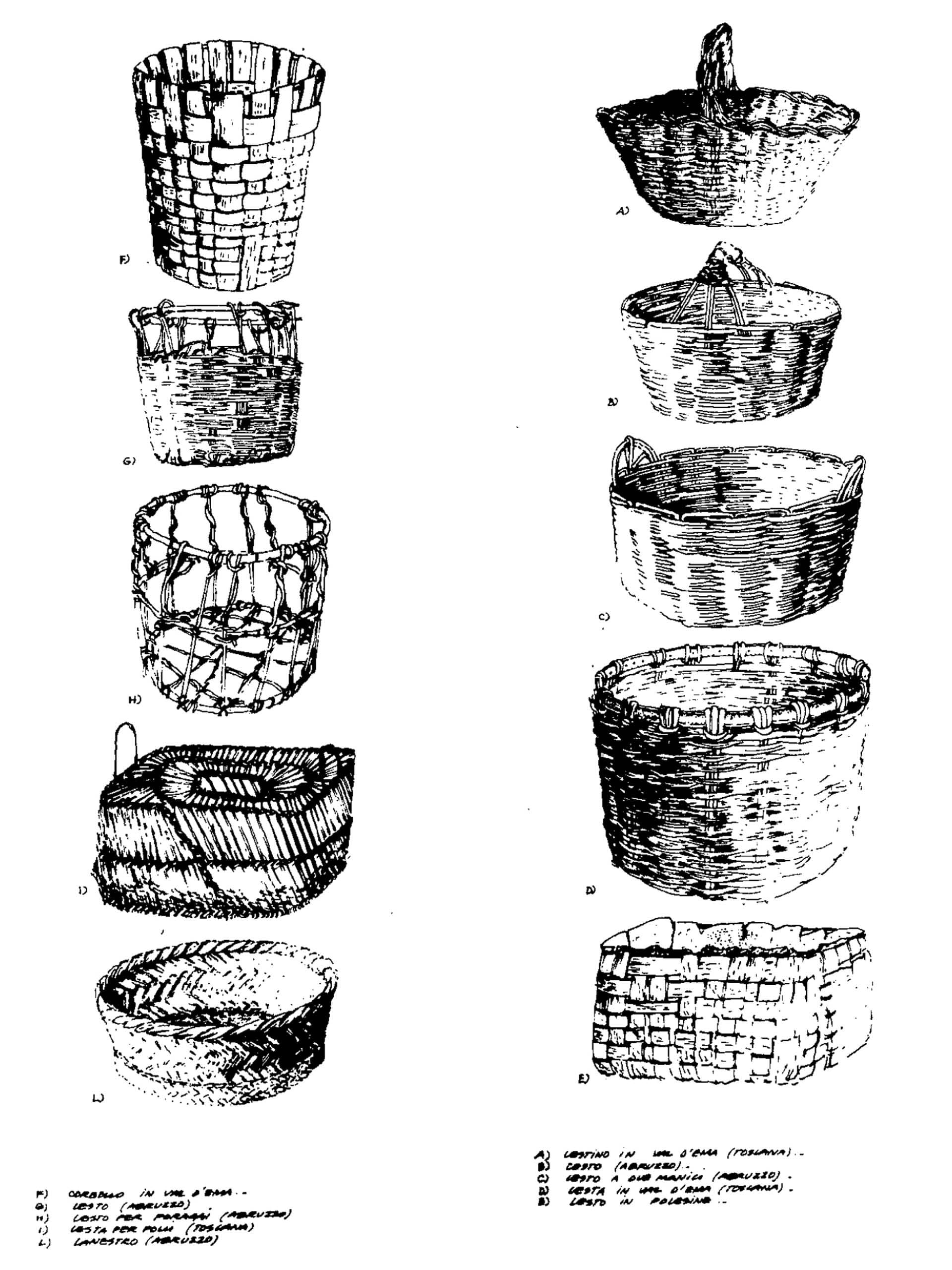

How is it that Superstudio—an architectural laboratory known for futuristic visions such as the Continuous Monument (1970), a neutral, totalizing infrastructural grid enveloping both cities and rural landscapes, and collages like Highway Earth-Moon (1973–74), which anticipated the so-called information superhighway—found itself, just a few years after its radical heyday, dealing with the bigoncia of Settignano and the Tuscan nottolino? (Respectively, a wooden bucket used for grape harvesting and a stone pin, perhaps—it’s hard to say for sure.) We are already in the realm of paleontology, and Google offers little help. This, in itself, confirms the thesis of Adolfo Natalini, Alessandro Poli, and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia: The designer is a sort of paleontologist who documents, in this case armed only with a pencil, the tools of a nearly vanished peasant world.

By carrying out this operation as part of a university course, the members of Superstudio demonstrate a strong sense of history, as well as an awareness of the risks of historicization: “When the projects and images, the writings and objects, of radical architecture were being produced, radical architecture did not exist. Now that this label exists historically, radical architecture no longer exists.” At a moment when disciplinary branding obscures the future once prophesied by Superstudio, it is to the past that we must turn. The avant-garde must go back to school, as the strategic detour no longer works. Unlike those who continue to perform counterculture from the cushioned balcony of culture, Superstudio understands that “irony, provocation, false syllogism, terrorism, mysticism” are necessarily tools of marginal actors, while in the institutional mainstream all that remains is memory, melancholy, and “the coincidence (the identity) between memory and project.” Dieses ist lange her, “now this is lost”: a similar sentiment had been expressed years earlier by Aldo Rossi. Superstudio knows that all that remains of radical production is a “paper cemetery.”1

Cavart, Riccardo Dalisi, A. De Angelis, Global Tools, Gruppo Teoria, Ugo La Pietra, Alessandro Mendini, Adolfo Natalini, Franco Raggi, “L’architettura radicale è morta: viva l’architettura radicale,” Spazioarte, nn. 10-11 (June-October 1977).

The aim of the course was to fight bourgeois dogma by reasserting the autonomy of popular and peasant culture through an analysis of alternative design methods capable of mediating the complex relationship between nature and culture: “Man has transformed nature into culture by using it in a way that is consistent with its laws.” Here, Superstudio was denouncing the exploitation of natural resources, but more than half a century later, a reading inspired by Jean Baudrillard (a reference already present in the collective’s thinking) seems even more timely. Today, nature is symbolically subjected to culture: The stylized illustrations of peasant tools are not so different from those adorning the surfaces of industrial products, especially green and organic ones. This may be due to the fact that, as design historian Valeria Bucchetti explains, “The food product, unlike other products of industrial design, ultimately has very little to say through its image or the physiognomy of its reference universe.”2 In truth, it has a great deal to tell (to recall Bucchetti’s examples: preparation, ingredients, the producer’s labor, and so on), but it cannot do so directly, so to speak, in a “non-simulacral” way. Even the most traditional and sincere company would end up clashing with the demands of the imaginary. Who (perhaps only Superstudio) would be enchanted by sterile plastic basins and cold steel pipes?

Valeria Bucchetti, Packaging design: storia, linguaggi, progetto (Milano: FrancoAngeli, 2005), p. 38.

All that remains is to interpret the meaning of Superstudio’s pencil journey in the face of a symbolic culturalization of nature. What becomes of the Abruzzese staio once it enters an encyclopedia of endangered practices? A rather recent cartoon, also composed of various silhouettes, frames the issue perfectly. On one side, we are asked to recognize famous brands based on their logos; on the other, we are asked to do the same with plants, starting from their leaves. Unlike the latter, the former are obvious. “Here is a slap of reality,” the cartoon states.

Superstudio writes: “What is fundamental is the sign-exchange value. . . . A real theory of objects and consumption must be based not on a theory of needs and their fulfillment, but on a theory of social performance and the production of signs. . . . Natural myths are replaced by fetishes of industrial products.” The reference to Baudrillard is clear. But the French philosopher knew that natural myths reappear in the form of simulacra, thus replacing one fetish with another, just like in the circular time of agricultural seasonality:

The very “rediscovery’"of the body is a corporeal recycling; the 'rediscovery' of Nature, in the form of a countryside trimmed down to the dimensions of a mere sample, surrounded on all sides by the vast fabric of the city, carefully policed, and served up 'at room temperature' as parkland, nature reserve or background scenery for second homes, is, in fact, a recycling of Nature.3

— JEAN BAUDRILLARD

Jean Baudrillard, The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures (New York: Sage Editions, 1970), p. 100.

Not only the quaint little world of television commercials, then, but also rural objects for tourists of the “slow life.” Is this simply a loss? It would be too nostalgic to think so. What we lose in authenticity—the natural myth—we gain in symbolic density: the brand. Today, the Lacoste crocodile carries more reality than a maple leaf or a Salento hoe. What the designer and researcher Michele Galluzzo calls “logos in real life” simply are real life.4

Michele Galluzzo, Logo In Real Life: Note per una storia sociale della visual identity (Brescia: Krisis Publishing, 2024).

After all, Superstudio presents the tools on a white background, detached from their context of use (except for one drawing that shows the farmer’s position), and thus they are already icons, logos. Their role is that of a “mental reagent for processes of self-analysis in a liberatory therapy for creativity,” wherein “minority cultures propose a surpassing of official aesthetic codes and technological taboos.” Their function is psychoanalytic, a dimension always central to Superstudio, which starts from the very idea of trauma: “Objects were meant to enter the sleepy homes of the Florentine and Italian bourgeoisie like Trojan horses, to provoke the same shock in them that we had experienced upon seeing water inside Florence’s monuments,” said Cristiano Toraldo di Francia elsewhere5. Therapeutic objects, then. Perhaps nothing more than sedatives for our ultra-technological and hypermodern civilization. This is what Gui Bonsiepe denounced in 1974 in the pages of Casabella: “A therapy to occupy the children of the welfare society [ . . .] the return to craft techniques and to a sectarian type of society, the manufacture of amulets . . . does not change a technological society, but merely gives it a more simply graceful appearance.”6

Chiara Alessi, "L’alluvione di Firenze e l’architettura radicale," Cosa c'entra?, episodio del podcast, Il Post, 6 novembre 2023, https://open.spotify.com/episode/02PwPh94ZhID46bjZH6U1Z

Gui Bonsiepe, "Una terapia per occupare i figli della società del benessere," Casabella, n. 389 (1974): p. 44

What remains of Superstudio’s journey? Others have followed in their footsteps, aligning not only project and memory but also memory and future. Belonging to this retro-avant-garde is the Lucanian graphic designer Mauro Bubbico, who in his posters for bakeries, carnival celebrations, and hyper-local patronal festivals recovers the signs and meanings of folklore, digitally radicalizing them. Drawing inspiration from the subversions of Dutch graphic design and even from generative design, Bubbico achieves an essentialism that recalls early-2000s clip art. In some works, he operates like a vector Matisse; in others, he sifts through pixels like a miller.

Then there is the Apulian artist Nico Angiuli, who, with his project The Tools’ Dance (2011-2017), recovers the more or less mechanized gestures of seasonal laborers working with tobacco in Albania, olives in Spain, and tomatoes in southern Italy, transforming them into dance choreography. By showing that agriculture is still living, pulsing, he shatters the amber-hued simulacrum of the good peasant. In doing so, he remedies the “theft of creativity” that, according to Superstudio, accompanies the “progressive proletarianization” of farmworkers.

Oscar Wilde claimed that one only finds in nature what one has hidden there in the first place7. Superstudio buried its radical critique—now tinged with melancholy—of hegemonic culture within it. But today, as hegemonic culture has devoured minority cultures by reducing them to symbols, nature hides something else: the equivalence of opposites and the truth of the simulacrum, the roboticized peasant and the sincerity of Mulino Bianco’s Macine biscuits.

Oscar Wilde, The Decay of Lying and Other Essays (London: Penguin, 2010).

We would like to thank Archivio Lara-Vinca Masini and Centro Pecci Prato for their invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article and for providing the images reproduced herein.

Silvio Lorusso is an Italian writer, artist and designer based in Lisbon, Portugal. He published Entreprecariat (Onomatopee) in 2019 and What Design Can’t Do (Set Margins’) in 2023. Lorusso is an assistant professor at the Lusófona University in Lisbon and a tutor at the Information Design department of Design Academy Eindhoven. He holds a Ph.D. in Design Sciences from the Iuav University of Venice.

The images come from the research Extra-Urban Material Culture (1973-1978) conducted at the Faculty of Architecture of Florence by Adolfo Natalini, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Poli, Michele De Lucchi. All images courtesy Archivio Superstudio. Originally published in Modo, March 1978.

finanziato dall'Unione Europea - Next Generation EU