At the Threshold of the Image

In his At the Threshold of the Image: From Narcissus to Virtual Reality — recently published by Zone Books — Andrea Pinotti traces the genealogy of a millennial desire: to transgress the boundary between representation and reality. From ancient illusionistic painting to VR headsets, the same impulse recurs toward images that aspire to become immediate presence, to dissimulate their mediated nature. Pinotti calls them "an-icons" — a paradox that cuts across different eras and technologies, from pictorial framing to virtual immersion.

You position the myth of Narcissus as a paradigm for your book. How does the ancient figure continue to inform our experience of the image, and how might it be employed to interpret our contemporary condition?

The actual point of departure was Chinese mythology, specifically the celebrated legend of the painter Wu Daozi, who vanishes into his own painting—a tale that circulated widely among Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, Siegfried Kracauer, and Béla Balázs. Yet when I began investigating the broader genealogy of the desire to transgress the boundaries separating image from reality, I could not avoid turning to Narcissus. It is an ancient myth that, through psychoanalytic interpretation, extends into our present moment, and in certain respects pervades it. The compulsion toward selfies, self-representation, and neurotic-obsessive device-based mirror play can be read through this narcissistic complex, which has roots in a distant—perhaps timeless—past, the time of myth. I always hesitate when people speak of anthropological universals. It often seems to exceed the necessary bounds of saying, “This holds for this culture, in this time, in this place.” Nevertheless, I’ve been struck by how powerfully this theme resurfaces across cultures—Chinese, Greek, Indian—as though the desire to traverse the image has assumed different forms throughout human history, contingent upon available technologies. Not least, Narcissus perishes within the image of himself into which he plunges—at least according to one version of the myth. I believe this detail appeals to those who persistently invoke anxiety about emerging technologies. I am continually struck by how certain formulations of fear recur. When photography was invented, and when artificial intelligence emerged, the same dread of the “loss of the human” resurfaced.

Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts, Trompe l'oeil. The Reverse of a Framed Painting (1670)

The genealogical reconstruction you offer in the book of this desire to enter, to immerse oneself through myths, stories, and fables across various epochs, places, and geographies, is fascinating. The book traces the wish to cross the threshold as predating the modern distinction between art and non-art. Within this broader tendency toward immersion, how has the specificity of the artistic field come to be defined—its manner of positioning itself in relation to this undercurrent, whether by resisting it or engaging in dialogue with the general regime of images? In what way does art and the discourse surrounding it articulate itself in relation to this fil rouge of immersion and emergence?

Art has been a fundamental interlocutor. From the outset, it was evident that my book could not offer a general theory of the image. Even a cursory examination of art history reveals that what I am attempting to reconstruct constitutes merely one chapter—a significant one, certainly, but by no means an exhaustive one. The entire theme of the image that negates itself—that is, the aniconic—or that tends to present itself directly as an object within the environment, as in trompe l’oeil or illusionistic painting, pertains to that lineage which over the centuries we have known by various names: trompe l’oeil, illusionism, mimesis, naturalism, hyperrealism. By contrast, so-called abstract art—at least in its Kandinskian lineage—strives to affirm its nature as a pure image, without reference to anything else. Abstract art presents itself as an autonomous presence, in which meaning takes shape and can exist only within that image. For this reason, it cannot be assimilated to the class of aniconic images that negate their own status as images. With regard to these latter, I have examined the strategies of de-framing: I mention Carlo Crivelli and his painted flies, but also Orlan, who had herself photographed while attempting to step beyond the frame. Throughout the centuries, artists have in various ways interrogated and challenged the boundary of the frame. The twentieth century was obsessed with the frame. It is telling that Georg Simmel, in 1902, emphasized its importance, declaring that this device enables us to understand that particular1 things transpire within it. Yet this is akin to closing the stable door after the horses have bolted: for decades, artists had been painting upon frames, extending images beyond their limits and allowing them to overflow—or, conversely, bringing the world, reality itself, into the image, as in Cubist collage. If the twentieth century was obsessed with the frame precisely because it had already lost it, the twenty-first century is obsessed with the screen. There exists an entire field of media studies termed “screenology.” When one dons a virtual reality headset, perceptual awareness of being in front of a screen is weakened: the device is there, yet it ideally seeks to make one forget its own presence, deluding us into believing we are inside the image, as if the support did not exist.

Georg Simmel, “The Picture Frame: An Aesthetic Study” in Essays on Art and Aesthetics, edited and introduced by Austin Harrington, 148–153, Chicago, University of Chicago Press (2020). Originally published as “Der Bilderrahmen. Eine ästhetische Untersuchung,” Kunst und Künstler 1 (1902): 297–301.

Fotoplastikon in Poznań, Municipal Gallery Arsenał – November 2014

Your book prompted me to consider how, from the disciplining of perspectival vision to the pedagogical function of museums, the frame becomes part of a broader process of constructing art as an autonomous space. Is this also a terrain upon which your reflection unfolds?

This is a theme that also concerns the institutional theory of art. Framing is always a device of delimitation, and therefore of threshold. We think of the museum or the gallery as devices beyond which we expect to encounter special objects. From this point of view, the experience has much in common with the religious one. If we look at the etymological root of the Latin templum or the Greek témenos, we find the Indo-European root tem-, meaning “to cut”: to carve out a sacred space as opposed to a profane one. After all, the frame—both that of the individual artwork and that of the institutional space containing other frames—performs an operation analogous to the demarcation of sacred space. I have insisted greatly on the question of de-framing, as well as on the disappearance of the awareness of being in front of a screen—another way of expressing “transparency of the medium,” or “immediacy.” It is obvious that nothing is ever immediate: every experience is mediated. But the paradox is that these are hyper-mediated, hyper-sophisticated technologies, employing the highest degree of complexity precisely to make us forget their presence. Another idea that has guided this research is “presence.” When one wears a headset, one is present within an environment rather than in front of an image: hence my notion of the “environmentalization of the image.” The things encountered there appear present, tangible, manipulable—not merely iconic placeholders. This has interested me because it reactivates archaic modes of experience—for instance, the Eucharist. In the Eucharist, the bread does not represent the body of Christ; it is the body. New technologies, perhaps unconsciously, revive dreams and desires elaborated over centuries by religions. Think of the teleportation of saints: the user seated in a gamer’s chair who “flies” inside Notre Dame Cathedral reenacts the dream—or the miracle—of bilocation. Saint Francis, who was in Assisi while at the same time appearing in Arles to assist Saint Anthony during his sermon.

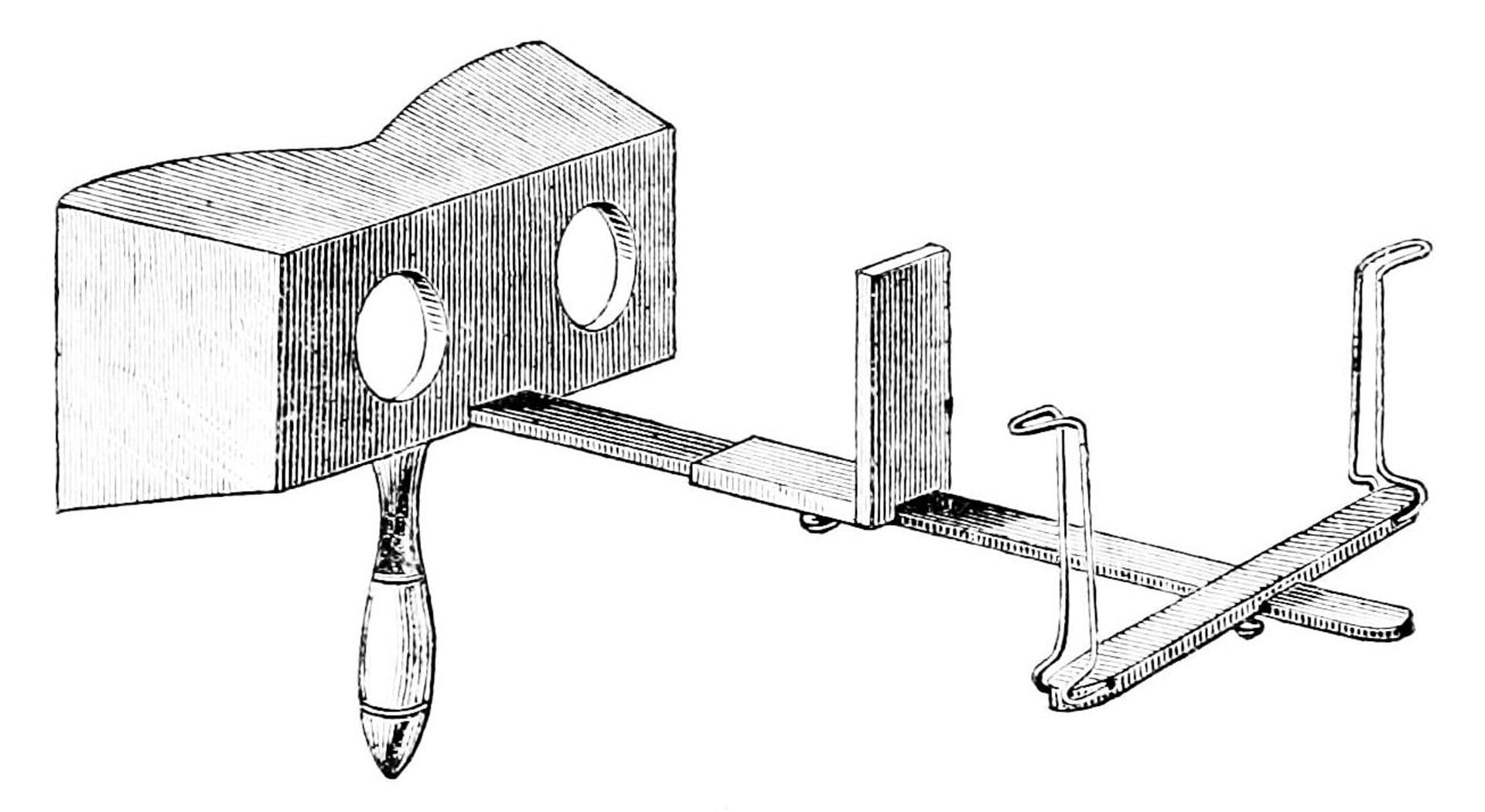

New form of stereoscope (1878)

In the book you also trace a genealogy of optical devices—from the panorama to the stereoscope—that embody the desire for immersion and anticipate virtual reality. This brought to mind, perhaps by contrast, Walter Benjamin’s notion of phantasmagoria: another form of optical spectacle that he employed as a metaphor for the seductive power of commodities. Do you perceive any common ground there, or is it a misleading kinship?

Phantasmagoria is a fundamental concept. The lineage you mentioned—from Marx in the first volume of Capital to Benjamin in The Arcades Project—employs phantasmagoria as both an optical device and a powerful metaphor. Yet if we look at the device itself, phantasmagoria is connected to a technology of “environmentalization” of the image that is rather different—if not opposed—to virtual reality. In VR—consider the headset—the device isolates the viewer from the surrounding world: one cannot even see one’s own hand, bodily perception is lost, and one enters an alternative, synthetic world. In the nineteenth century, its closest relative was the stereoscope. Looking at certain photographs of Victorian women using stereoscopes, one realizes that they isolate themselves completely, entering another world. Yet this is not the only way to access a virtual reality environment. There are also the so-called CAVE systems—Cave Automatic Virtual Environments—spaces entirely covered with screens, where one continues to perceive one’s own body. These are the closest kin to the panorama: in the panorama, one would walk on 360-degree platforms, continuing to see others while being immersed in a painted world. It is interesting that panoramas continue to be built. Yadegar Asisi’s panorama in Berlin, dedicated to the Pergamon Altar, is a cylindrical tower hosting ultra–high-resolution photographs, with lights that change according to the time of day and multichannel sound. It is a highly intriguing experiment. By contrast, nineteenth-century phantasmagoria was created through the projection of spectral figures by means of magic lanterns—an experience more emergent than immersive, analogous to today’s augmented reality.

The book also returns to the theme of empathy, which appears to be resurging powerfully today within the field of immersive technologies. I’m thinking of “empathic journalism,” or certain VR-based artistic experiences.

Empathy has long been one of my research interests, to which I devoted a study tracing its historical evolution (Empatia. Storia di un’idea da Platone al postumano, Laterza, 2011). It is significant that the advocates of virtual reality have taken up and relaunched this notion, especially within immersive journalism. The idea was articulated above all by Chris Milk, author of videos for the United Nations such as Clouds Over Sidra (2015): thanks to the immersive effect of this work, one is no longer “in front of” a screen showing the Syrian civil war, but “inside” a refugee camp in Jordan. The experience consists of being able to turn one’s gaze 360 degrees while listening to the voice of Sidra, a young girl who fled the war and recounts a typical day in her life. Milk describes VR as “the ultimate empathy machine” and presents his immersive films in geopolitically significant contexts such as the World Economic Forum in Davos, convinced that such engaging experiences can elicit empathy in those who hold the power to intervene in humanitarian crises. Alejandro González Iñárritu has also worked in this direction with Carne y Arena (2017), which transports the viewer into the desert between Mexico and the United States, among a group of South American migrants attempting to cross the border illegally. Similarly, Kathryn Bigelow produced a VR video about rangers fighting elephant poaching. When asked why she had not chosen to make a traditional film, she replied: “The ultimate reason for my choice is the question of empathy.” All this, however, has an evident limitation: current technologies still do not allow for a truly dialogical dimension. One listens to Sidra, and while it is true that one can move within the visual space and have the impression of sharing her peripersonal space, the narration always remains the same, and one cannot genuinely interact with her as with a real interlocutor. From this point of view, virtual reality shares something with what Roland Barthes says about photography: it is an image of the past that tells us “this has been.” This aspect too invites reflection on the limits of the much-celebrated interactivity: if freedom consists in choosing among a set of options predetermined by the author or the programmer—whether two, two hundred, or two million—it nevertheless remains a conditioned freedom.

Technical Museum in Brno, Panorama exhibition at the TMB

Andrea Pinotti teaches Image Theory at the University of Milan, where he serves as Director of the Department of Philosophy “Piero Martinetti.” He coordinated the ERC Project An-Icon. An-iconology. History, Theory, and Practices of Environmental Images (2019–2025). His research focuses on theories of the image and visual culture; theories of collective memory and monumentality; theories of empathy; the Goethean morphological tradition and its contemporary developments. Together with Antonio Somaini, he co-authored Cultura visuale. Immagini sguardi media dispositivi (Einaudi, 2016), dedicated to visual studies. His books Alla soglia dell’immagine. Da Narciso alla realtà virtuale (Einaudi, 2021) and Nonumento. Un paradosso della memoria (Johan & Levi, 2023) explore immersive image-making technologies and their genealogies. His most recent book is Il primo libro di teoria dell’immagine (Einaudi, 2024).

Francesco Tenaglia (Chieti) is an educator, curator and a writer.

finanziato dall'Unione Europea - Next Generation EU