Every Elevator Available

In April 2022, Hanne Lippard and Francesco Cavaliere met in Milan to record a conversation and some of the material for her record The Talk Shop. Now a new conversation has started, which partly resumes the previous one and discursively explores the semantic and psycho-acoustic values that language, the silence before a response, and the body that absorbs the word possess in the transitory moments of everyday life.

If I talk to a static surface—to the floor, for example, or if I do it through the air, apart from the alphabetical concatenation of the sentence, apart from the possible religious value that stays between the waves, what language carries on after the sentence goes through? After its silence.

If the conversation between two receivers waiting for an answer happens, does something actually change? “Non sei andata a scuola? Ba no!” (Have you been at school? Yes, sure!) In certain parts of Tuscany, the exclamation “No!” has an opposite meaning and magically becomes “Yes!” like a well-done litotes can. But I don’t want to talk about that. Each language has idioms and ways to spin things around. Here I’m asking if language can carry on something that goes over the etymological aspect of the words, even when nobody is actually listening. It sure does! And I believe that each silence between words can be a reinforcement of what comes right after. I’m saying that because I’m writing something after I have already said it, exchanged, recorded, and for a second I don’t really see the purpose. Why should I write something about something that is already done, recorded, forgotten? But let’s take a step back. If you say something, like a friend of mine used to say, if you name it out loud, that thing should appear. If you say “wolf,” for example, a wolf will materialize. But how many are there? Wolves are never alone. How hungry are the words describing its appetite? This seems not transpiring from the name transported by the air into reality; only magic will stop me with this nonsense.

The description of reality is never enough to mirror reality itself. What is that hint that lurks between one sentence and another, that thing that is neither the meaning nor the acoustic image of the thing it is meant to represent?

I’m not sure why, but cyclically I end up rolling with Alfred Korzybski’s general semantics. Hey look, there’s a hill there! The hill appears in our minds, probably with all the characteristics that a hill has or can have. But it is the timbre of the voice that tells us about it—its intensity, its form, its extension. Or is it then the words, hatching, sloping, greening, that precisely describe its color, its unfolding in the landscape? What do we remember most easily? The voice, or the words being spoken? In fact, it is the timbre of the voice that tells us whether that particular wolf is hungry, or tame, or frightened. It certainly won’t tell us why. But then I think that words and their meaning may actually be the most overpowering thing, definitely the most incisive element for our bank. I don’t know, it depends.

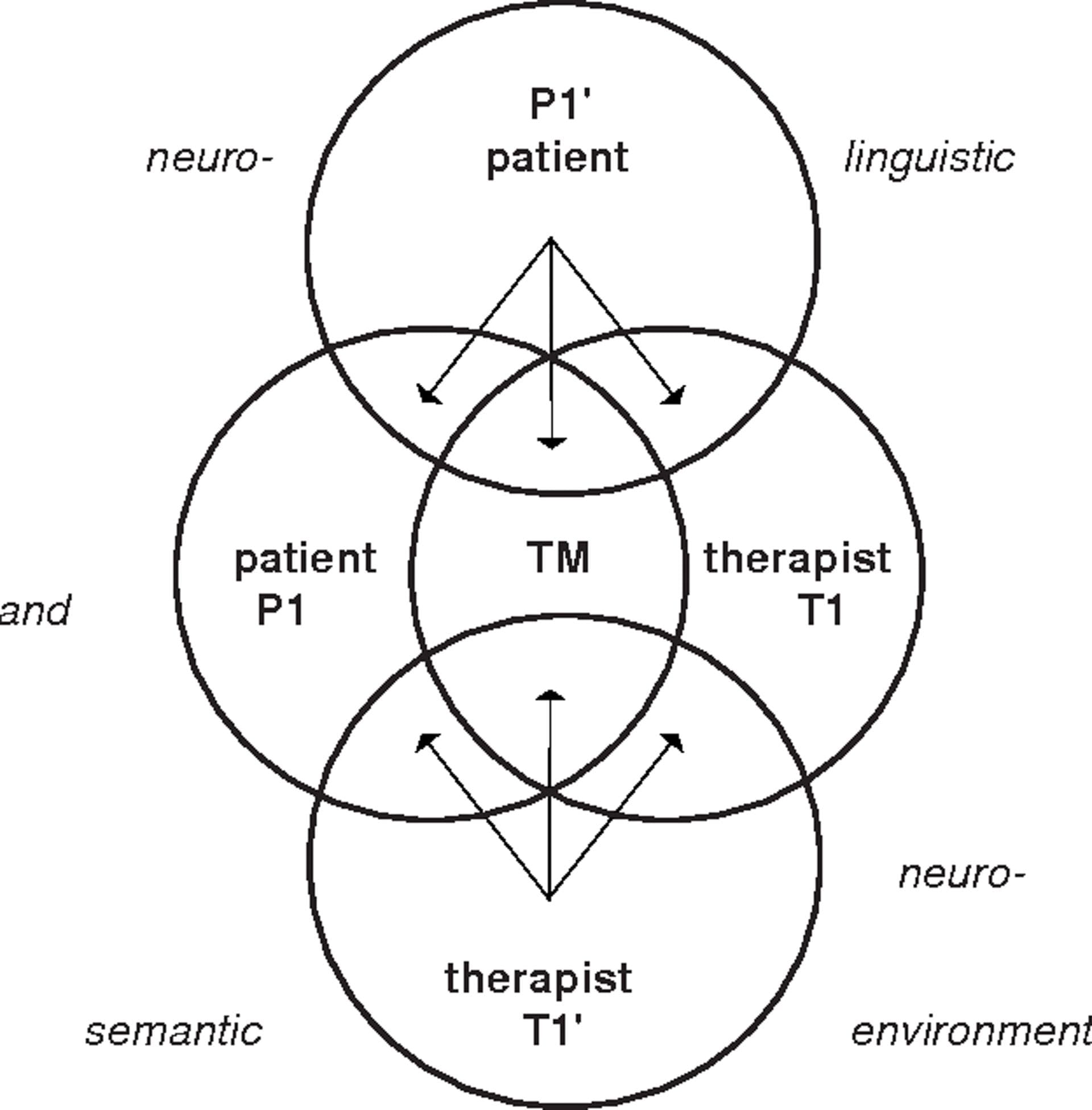

diagram - figure 1 - general semantics - semantic and therapy

Let’s say our languages are made up of a layered overlay of timbre and signifiers that when stripped of meaning can detect a new linguistic structure—pure, full of everything that is not descriptive, analytical, conceptual. Something never heard before. For a moment I wish I had an application, an audio program, that would separate every single phoneme from the words of a long conversation in real time. It probably exists. I would like to have two horizontal diagrams made up of spherical-oval icons, walking hand in hand: a red one for the phonemes, a light blue one just below for the compound words. Between these flowing blocks, I imagine discovering tiny roots growing and connecting the two parts, threadlike, fine.

What information do phonemes and words exchange? Like cursing something? Turning the sentence around? If a speech turns into a phoneme while maintaining its dynamics, pitches, and durations, we can say that we are dealing with a glossolalia, a long lalla, which extends with its pauses from A to B, including repetitions, themes, refrains, all the ornaments and redundant repetitions that we have in our conversations. But is the word, when stripped of meanings and signifiers, really simply a beautiful grammar of several sounds? Mmm, back to our wolf for a second. If we imitate his verse, his vocal gesture, let us do so with an E minor attack that from pianissimo suddenly rises sharply, then descends into a short pause of a beat.

Are we so sure that this can express that particular concern? Fear, anger? What if there was no one listening to that wolf, observing that hill? What if that yowling began and ended between the ground and the grassy boulders around it? What if observing the hill was nothing but a house reflected in its silence? Here words or signs would be useless to describe it. About the conversation with “Anna Leopardo,” Hanne Lippard and I remember several things: There was a change of plan, a phone call, an address to look up on a map, timetables and trains to catch. One or more metro stops.

The anteroom of the recording booth, a few papers, two microphones. The leopard was silent. In addition to the many air trails that, by “his” own admission, deliberately snake in and around “his” texts, that same question posed at the beginning of this introductory “hat” tried to articulate itself without reaching a resolution of its own. What does language bring with it? Geography, conversations, encounters. But here too, in that situation, the word and its voice were not fully identified with a precise if, but with labials, extended sibilants, controlled dentals that slowly rise between the pause seconds of a paper just seen descending. It is difficult to transcribe that, the breath that registers the things. If the timbral value increases the perception of the word, then can the word l-e-m-o-n trigger more saliva than a drop of its juice on the tongue?

—Francesco Cavaliere

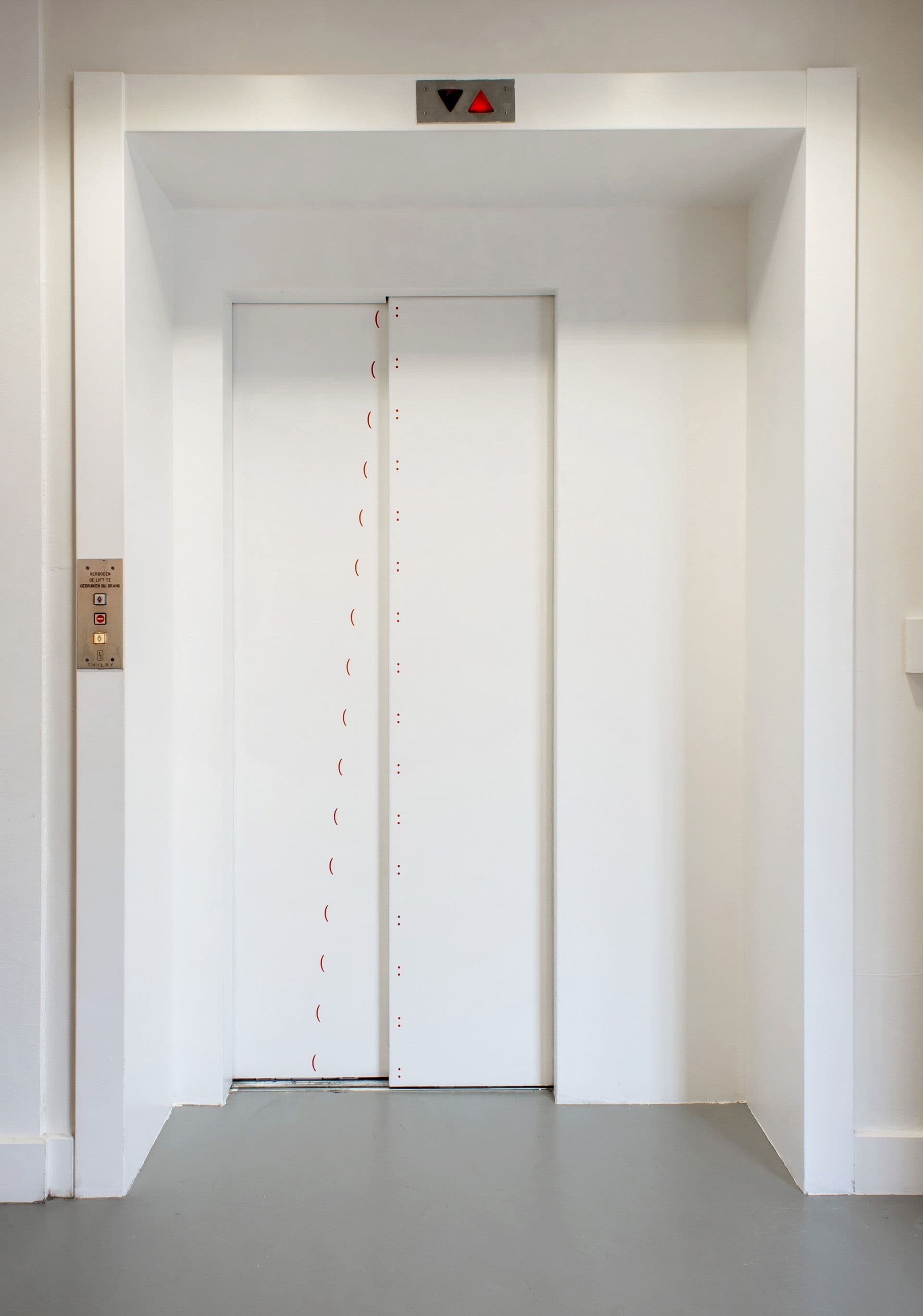

So, I wrote you this about the escalator piece, you know? And I saw the etymological meaning of the escalator in different lands and languages and where this word comes from, for example, elevators; to let someone rise up or, for instance, somebody planning to climb a mountain and things like that. And I’m wondering, why did you choose this particular word, since it’s also a constant movement, almost like a loop? Do you choose this word because you have a specific picture, an image, or is it more like a feeling, more like a separate thought you want to elevate somewhere?

I think it’s interesting to ask about the escalator because recently I took a lot of videos of escalators, when I was traveling. I think it’s a very particular movement, because it’s not very fast in relationship to other technological artefacts—you know. It has to move at a pace that people feel comfortable with. Not too slow, not too fast, so, somewhere in between, you know, a vehicle, it’s a vehicle, but it’s not moving so much faster than a human body. And the work, “Every Elevator” it basically came from communicating with a museum, an exhibition I had at MUDAM in Luxembourg, where I said… One of the emails was about, I have a work for escalators which is on the escalator doors, and in the email, I asked, Can we place the work on more than one escalator? and the email reply was: every escalator available. And I really liked the sound of it, every escalator available. So I just thought… Also, wait, no, sorry, was it every elevator available. Sorry, every elevator available, every elevator available, and it just became like a loop in my head and also like the idea of this—this limited availability. In front of an elevator, you’re standing there waiting for it, sometimes you wait for an elevator for like ten minutes, right? It’s sort of a strange thing. You’re just standing there waiting for a door to open. I think in general there’s something in my work that I have not really put my finger on which has to do with these kinds of transitory spaces, like escalators, elevators, staircases, just like the spiral staircase at my show at KW in Berlin. There’s a fascination for this carrier of human bodies, which is not like a car, you know, more like an ascent or a descent.

So it’s like almost the same thing but actually it isn’t, the elevator, which is also a box, it’s like a super-silent box. In the silent box we feel part of the place, we become one of the walls. A place where you are on your own, if you are on your own. When you’re with somebody you don’t know, then you try to keep it as silent as you can, try to be invisible, you don’t want to interact. What about this combination of a silent place and being by yourself? What do you think about it?

I think it’s a very particular social space, the elevator. It’s very much exactly as you say, this awkward moment where you’re in an enclosed place with a complete stranger that you wouldn’t even usually engage with… Also sometimes if you have a formal meeting with someone or you’re meeting someone new and you have to be in an elevator together, somehow something happens in this elevator, there’s always this awkwardness. I also think about elevator music, this idea of trying to make this space less awkward by filling it with a sound. I mean, it has its own terminology right? “Elevator music,” this unpleasant nondescript music

I feel that whatever you say in that particular place with an unknown person, the words gain a new value, the speech becomes somehow underlined. If I have to send an audio message to the elevator it’s kind of perfect… you know. You have this perfect silence, perfect timing, and you go upstairs. The elevator is definitely a special, nice recording place! I can picture you practicing your things, your texts that you may need to read. So, I’m curious about these transitory moments between spaces and your practice. Do you sometimes talk to yourself and if... you do have frequent sentences you repeat to yourself?

Hanne Lippard, Flesh, 2016, Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina; Installation view KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Photo: Frank Sperling

Hanne Lippard, Flesh, 2016, Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina; Installation view KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Photo: Frank Sperling

If you’d like to talk freely about this, I find it really interesting. When you first asked me this question, I couldn’t think about any moment where I actually do talk to myself. I couldn’t say when, or what words, and so on, but now I was very, very aware of it in the last twenty-four hours because we talked about it and realized how much I talk to myself and how I especially do it here in Rome because I don’t know so many people. I spend a lot of time alone, so I will say out loud, I’m so tired, but I mean, who cares? I also noticed, I sort of pick up, I did notice that yesterday, for instance, I got a bit obsessed with the way an American person in a film said— Mirror, where I realized that the way Americans say “mirror” is so confusing. And so I started just repeating the word “mirror,” “mirror,” because “mirror” in British is so different. There’s these moments where I get caught up in a sound, like “every elevator available.” Somehow it’s like all the other texts pass by my eyes on a LED screen and I don’t think about it until there’s suddenly one particular word or sentence and it’s a standstill. And then it almost becomes like a loop in the head, a sort of a extended pause on that word. And of course being in a foreign country… I mean yesterday, I was in Denmark and then suddenly I understand what everyone is saying around me without any effort, and somehow language becomes more present, like I’m understanding everyone, and here in Italy of course I don’t understand everyone unless I really listen. So it becomes different, I only hear the words I recognize, which is also a weird thing, no? It’s like a blackout of all the texts I don’t understand, but it’s like allora, va be, bo… Which is not a word, but, you know, like, all the words I understand.

Yeah, yeah, “bah.”

Yeah, “bah,” and you know, if you hear someone say something and you are almost like I understand this word, I guess this is also how you start to understand the language. It sort of unravels. Like the first week you understand three words, then in one month you maybe understand thirty words, and then… It’s a strange thing, because in Germany I used to be like this, I didn’t understand hardly anything, and now that I’m there, I understand everything, so I have no longer the incognito, it’s a strange, slow process.

Recording something, are you outside in the street and you just talk to yourself, or repeat something that you’re learning, a new language for instance? We basically work like a body recorder, like a child listening and learning a language. We do this, I think it’s pretty normal, if you talk to yourself, specific words because you are learning. It’s so basic, yeah, the mechanical process of it can be very frustrating. But we have this, I mean it’s obvious, the mouth, our ears, are there, but at the same time you don’t think so much about it, so we are surprised when we perceive how we get the outside-world information, we use something that we don’t recall.

Well, I notice that it’s very embarrassing when I repeat Italian phrases or I say something out loud to myself, when I notice somebody else noticing that I am saying something to myself. I always pick up my phone and pretend I don’t—I get—it’s a very—it’s so strange, it’s such an embarrassing—it’s like a sign of madness. It’s like you have no control over yourself in a way. No, I’m so tired, I can’t anymore, or something.

It’s almost like a box where you throw away your mistakes, your weaknesses, the words are invisible and you become your invisible therapist. It’s yourself and your language. The language has this power, almost like an exorcism, or something like it. You know, I don’t know if you should go through this again, but yes this question rolls in my mind and maybe it would be cool to go through it. When you see a microphone, do you think of it like an extension of yourself? Or is it just a tool to amplify yourself?

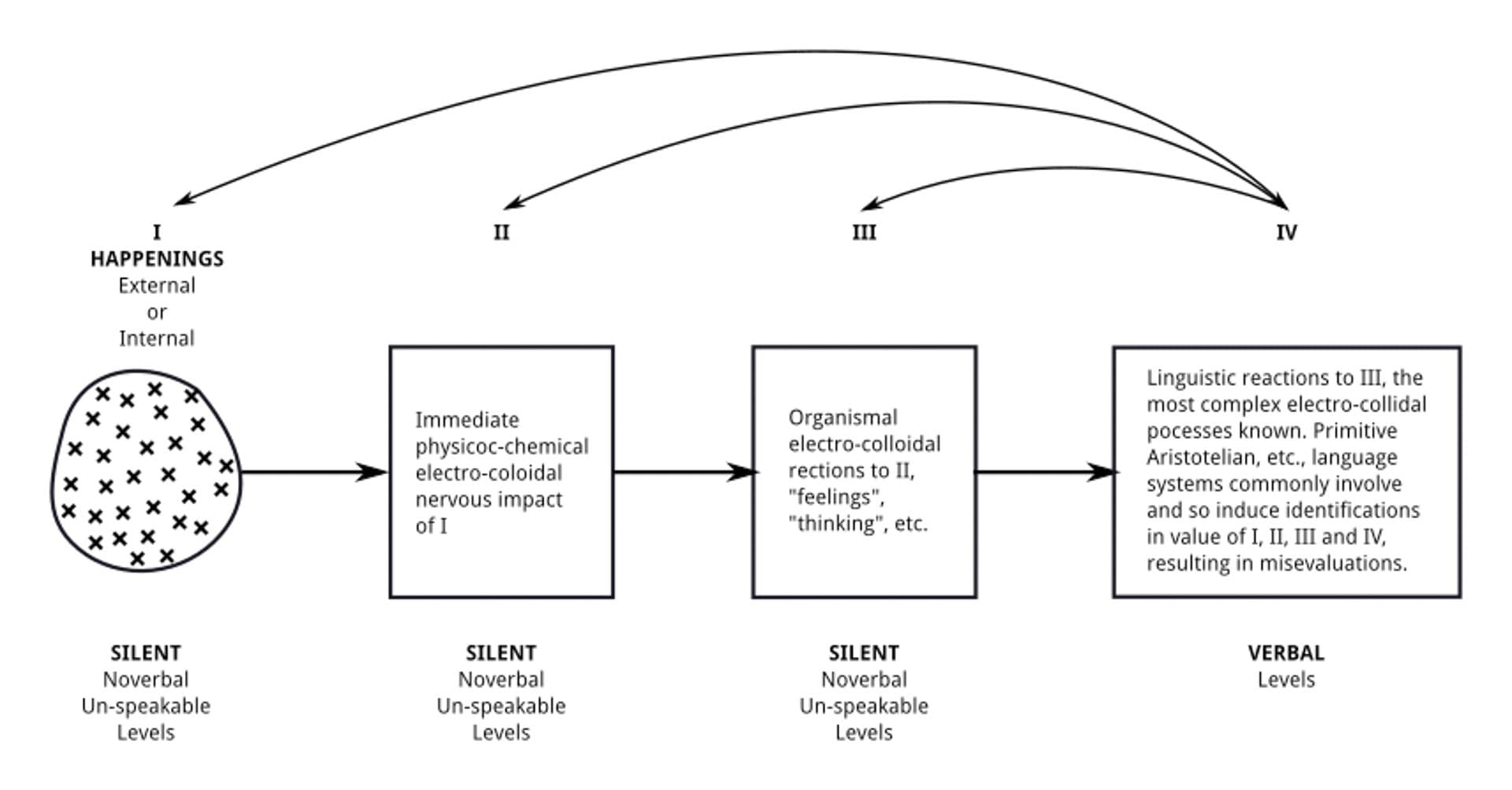

diagram - figure 2 - general semantics - semantic and therapy

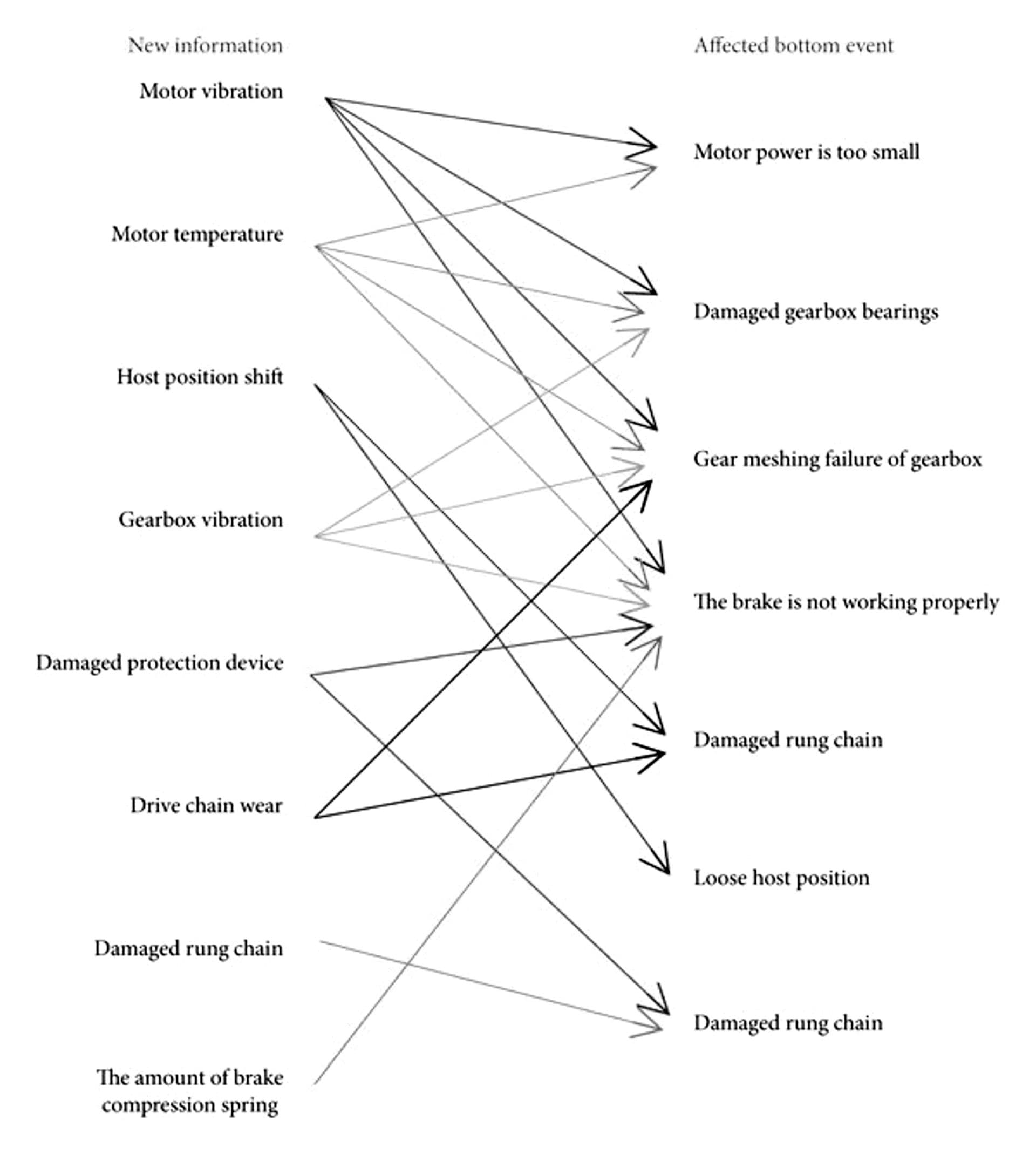

diagram - figure 3 - general semantics - semantic and therapy

I think it’s a tool for me to step out of my role as a human, as myself, as a person, and be able to be on stage, because there’s little else that is part of the act. You know, I don’t even necessarily—I wear something a little bit nicer maybe, but it’s also something I could wear on a normal day. I don’t do anything other than amplify the voice, but amplification for me is necessary in order to perform. Also I think it’s somehow a little bit of a—I don’t know if I would say ego boost, but like a confidence boost or something. There have been a few times where I’ve performed without a microphone, when it’s been in a small, intimate space. I feel like I’m not able to, it’s like I have this lack of power—I definitely—it’s not just a microphone. I do have a relationship to the microphone and knowing the distance and knowing how to sort of relate to it. And yeah, it almost becomes a dialogue with the microphone, because the amount of people in the room is sometimes so intimidating, or like just seeing people’s faces is so intimidating, and the microphone is almost like a protection, I guess, in a way, a protection and amplification, or like a confidence vehicle. I had a funny moment where a man, some weeks ago, who was a singer, was telling me how I should get a microphone that I always bring with me, he was being very mansplaining about microphones and I got so annoyed because I don’t know, I felt almost offended, because I’ve been working with this for fifteen years, and I also think it’s fine to have a variation of microphones. He claimed that you should only have this one microphone that you work with, and I don’t know, it was a strange encounter.

Yeah, a microphone, and people always say that a microphone is an extension of our body, but I don’t think so, I don’t feel like that. I’m rather close to what you are saying. It’s more like a shield, an invisible aura that suddenly becomes visible, very close, the voice, it’s only sound.

I mean, it’s also a way to fill the room in a way that sometimes people think, “Oh, okay, you’re just a single body in the middle of the stage.” You feel small if you don’t have a band or if you don’t have a large ensemble, not part of a larger theater, you know, a play or something. I think the microphone gives, feels, like a space that you can lean back on somehow.

Do you often use the microphone also without the audience, like a tool to store things, thoughts, notes, or things like that?

I don’t do a lot of recording notes, I have to say, not necessarily. But I do speech to text most of the time, which is very helpful.

Hanne Lippard, Flesh, 2016, Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina; Installation view KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Photo: Frank Sperling

How about the battery right now?

It’s fine with the battery.

Okay, okay, I’m saying, if you have any particular pleasure to use words because they have a strong image, so people can really see what you are saying? Or the sound and the vocabulary of the speech is much more important than the picture you want people to visualize?

I think it’s a dynamic between both. I mean, you’re playing with such minimal means, you know, if it’s purely the voice and nothing visual. There’s of course words that work with very particular images, I think, and then at the same time there’s the sound, but I think you can also go from—I mean, let’s take the last piece on the record, which is “Portal”, where I repeat the words ‘exits exist’ and I think “exit,” “exit” is like—I don’t know, it’s a strong word in a way. Somehow I think it’s also like now that this record has been recorded over two years ago, you know? Like when you have clarity about what it is at the end, I feel that these exits exist, that are very much also about being caught in this technological nightmare, or like this idea of efficiency and intentions and also, you know, the escalators not being autonomous. You’re not moving your own body, so the idea of having this track at the end of the record, you know, “exits exist,” it’s almost like a hopeful sort of “exits exist.” And then with repetition it becomes a blur of words, becoming sound rather than images. This is something I find very interesting to work with in general.

If you repeat “exit exist” so much, then “the exit” is going to be close, and I think we already have lots of material.

Hanne Lippard (NO/DE), *1984 in Milton Keynes, GB, lives and works in Berlin. Lippard’s practice lies at the confluence of spoken and written word and her work is conveyed through a variety of disciplines, predominantly sound-installations and performance. Her most recent performances and exhibitions include A Model, Mudam Luxembourg, Luxembourg (2024), Auditions for an unwritten opera, Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, Baden-Baden (2023) The Myths and Realities of Achieving Financial Independence, CCA, Berlin (2022); Le langage est une peau, FRAC Lorraine, Metz (2021); Contact, Mood, Share, MHKA, Antwerp (2021); X, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Carquefou (2020); RIBOCA2, Riga (2020); Our present, Museum fur Gegenwartskunst, Siegen (2020); Parades for FIAC, Palais de la Découverte (2019); Art Night London (2019); Inefficiencies, Goethe in the Skyways, Minneapolis (2019); There is Fiction in the Space Between, n.b.k. Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin, (2019); Nam June Paik Award 2018, Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster (2018); Ulyd, Kunsthall Stavanger, Stavanger and FriArt, Friboug (2018). Lippard has recently been awarded with the Preis der Nationalgalerie 2024 and is a Prize Fellow at the Deutschen Akademie Villa Massimo in Rome for 2024-25.

Francesco Cavaliere (1980, Piombino) is a visual artist, writer and musician. His work is developed in a polymorphous activity that overall aims to stimulate our collective imagination. He has collaborated with GAM Turin, the Museum of Contemporary Art Fondazione Serralves in Porto, the MANN in Naples, Una Boccata d'arte, the Liverpool Biennial, the Riga Biennial of Art, MAXXI Aquila, Triennale of Milan, Les Urbaines in Lausanne, Palazzo delle Esposizioni Rome, HAU Hebbel am Ufer in Berlin, Museet for Samtidskunst in Roskilde, Kunstmuseum in Lucerne, XING in Bologna, Club2Club in Torino, INFRA festival in Tokyo, BOZAR in Brussels, ISSUE Project Room in New York.

finanziato dall'Unione Europea - Next Generation EU