I consider myself to be a painter

In the fall of 2022, Catherine Breillat sat down with film critic Murielle Joudet in Paris. They met and spoke over several months, and the director traced her career film by film—from her 1975 debut A Real Young Girl to Last Summer (2023), her latest feature. The long conversation reveals how Breillat’s films tell her own story: they explore female sexuality, adolescence, and the shame that accompanies them. At the same time, Breillat engages with the gaze itself, as well as with the painters and writers who, she says, “extend their hand to her through the centuries.”

Their conversations, which continued into the following year, reveal Breillat’s enduring love for painters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. “I borrowed their soul, since the soul is what counts,” she explained. Her visceral films reflect this interest: they depict ecstasy, beauty, and pain. The book-length interview, I Only Believe in Myself, will be published by Semiotext(e) in October. Chiaromonte presents excerpts ahead of its release.

“My name is Alice Bonnard, I don’t like people, they oppress me.” Your cinema begins with these words. From the beginning, a character who only believes in herself, like all of your heroines: everything else is unreal. You film French reality like a jinxed nightmare.

That’s what the head of censorship said when he read the screenplay. He didn’t raise an eyebrow at the sexual stuff, it was the way in which I described, at the beginning of the film, the woman on the train; I had a take on society that was disagreeable, contemptuous, I was presenting a terrible image of France. But that wasn’t the subject. My subject was a little girl in the provinces who hated everything and everyone, except the boy she liked, whom she ultimately hated, too. The film may have been wild, but Hiram Keller, whom I had seen in Fellini’s Satyricon, was a star at the time. The grocer is played by Shirley Stoler from The Honeymoon Killers (Leonard Kastle, 1970). Mort Shuman composed and performed all the music. I don’t think that stars of that stature would have dared or have had the generosity to make that sort of a film today.

DETAIL FROM GUSTAVE COURBET, LE SOMMEIL (1866)

The film creates an extraterrestrial perspective of the young girl. Everything appears for the first time. You extend the dimensions of her body to the dimensions of the world: the vagina, the cerumen … It’s a life-form that you explore in a very clinical way, as if it were a medical visit. As opposed to a surface fantasy, an imaginary that doesn’t want to see the body with its hairs, its secretions. You reveal the gore buried in the young girl.

It’s like eXistenZ (David Cronenberg, 1999)! An aesthetics of slime that disgusts us and is intimately tied to the feminine. That’s what Cronenberg understood. I’m certain that he wanted to do that, reestablish slime as an aesthetic and moral value. My novel Le soupirail (The Basement Window) was tightly written, full of metaphorical images. Actually, I have to keep myself from writing alexandrines when I’m writing modern things—for me, the legitimacy of the French language can be found in the alexandrine. So the book is overrun with musical language; it’s when I had to make images out of it that it grew very com- plicated. For example, the little spoon that she sticks in her vagina … How do you film that? How do you ensure that the poetry of the book doesn’t become, once it’s filmed, prosaic? An image has to have a certain violence.

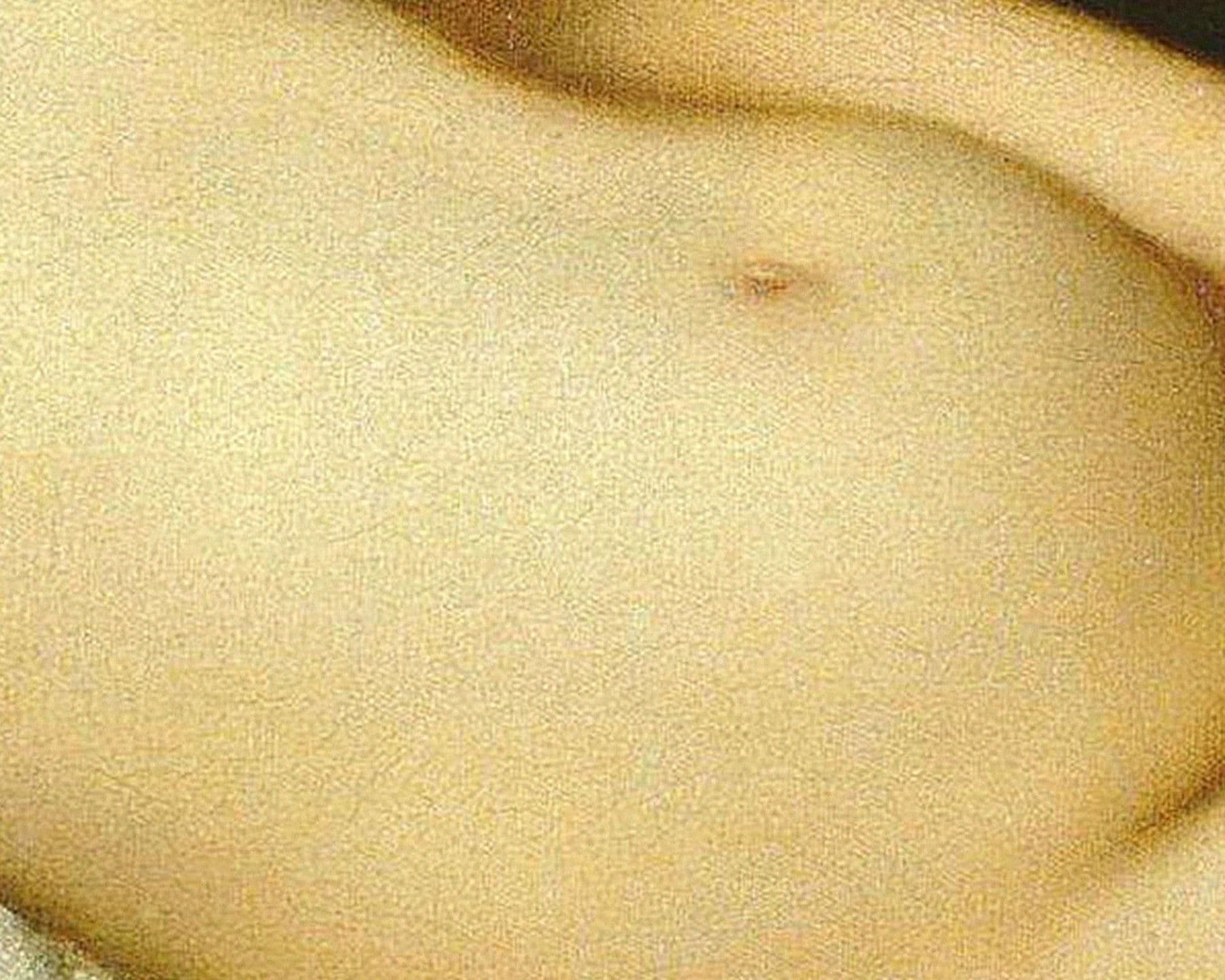

DETAIL FROM GUSTAVE COURBET, L'ORIGINE DU MONDE (1866)

How do you present ugliness in a film?

With A Real Young Girl, I decided that I wouldn’t use French colors, which were fashionable at the time. All of French cinema was predominantly beige or blue. I decided that the film would be multicolored, garish, that we would have a trailer covered in orange carpet that was in at the time, the ugliest thing in the world. I hadn’t ever been inside a trailer but I had wanted to confront that horrible universe people lived in. I sewed Alice’s T-shirt myself, it was turquoise, a color that was considered to be awful, and I added this absurd braided white rickrack to the collar. I dyed the bathing suit pink and black. I hate good taste—that belongs in a bourgeois salon, not in art. The only concern that the French censor had with A Real Young Girl was about my very negative opinion of the French population.

That hatred of France…

France is sycophantic and hypocritical and, what’s even worse, the slogan of the French Revolution is “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity for all men,” meaning no woman will ever be their equal. It’s France’s founding principle, the only country where royalty applied the Salic law: women can’t reign. Queens everywhere, except in France. They’d rather go and find some distant, hated cousin than have a woman rule. The hatred for women in France runs deep, so deep that they guillotined a revolutionary like Olympe de Gouges. Misogyny is in France’s DNA.

DETAIL FROM CARAVAGGIO, MARY MAGDALEN IN ECSTASY (1606)

Your films could be misunderstood as being about a right to pleasure or the female orgasm, although they’re never about that. They’re identity quests.

I never make films about the orgasm or about pleasure, I don’t care about that. That’s not what counts. There’s something more important. I’m searching for ecstasy, the transparent body, that state of nearly immobile ecstasy where you escape all material contingency. Penetration, sex, doesn’t interest me except as a means to realize the transparent body. Of course, it has to move through that, but what interests me is the passage from the trivial to the divine, that sensation of eternity. That happens very rarely and when it doesn’t happen, we shouldn’t deprive ourselves of the orgasm and pleasure. I couldn’t agree more.

I feel that it’s important that we specify that that isn’t your subject.

That isn’t my cinema at all. My cinema is about ritual. Idealism is ritual, we’re dealing with symbols of purity, divinity. Caroline is Joan of Arc, a saint on a crusade. Sexuality is simply the path to amorous abstraction. The path is sexual, that’s the way it is. But because we’ve turned it into a commercial, obscene object, we tend to forget that. I don’t know what eroticism is. Romance was made in a state of trance, we were aiming very, very high.

DETAIL FROM RAPHAEL, THE ALBA MADONNA (1510)

Is boredom only a thing for young girls, or are you still bored?

I don’t think I’m ever bored. Let’s just say that boredom is my way of thinking. That gives me an enormous amount of power, it’s a way of being with yourself. They say that cinema is a collective art, but it isn’t at all: the auteur is alone, absolutely alone. Now, less so, but at the time, a shoot seemed as long to me as when you tell a child that you’re leaving for two days—two days is forever. 36 fillette, despite being short, only six or seven weeks of shooting, seemed interminable to me. I couldn’t see the end of it and I was absolutely alone. For everyone else it was Club Med; I hated them because they were fooling around. You make a film alone, you don’t have fun. Your actor has to be available: if he’s having fun, he’ll spoil.

When you use actors to portray your relatives, do you think about the reaction that will provoke?

Christian Bourgois warned me. He said, “It’s crazy, everyone who hangs out with writers must know that they will, to some extent, show up in their work. They blame you not only because they recognize themselves, but because on top of that, it isn’t really them.” Obviously: you steal something from them and at the same time, it isn’t them, that’s the problem when you draw from your own life. Bergman, Proust, Miller: they did the same thing. You have no choice. My films are profoundly autobiographical and yet not that autobiographical: I amalgamate eras, one person with another, then I’ll add a news story. I don’t invent anything, just the order. I rearrange, but I don’t invent anything.

DETAIL FROM TITIAN, VENUS OF URBINO (1538)

You said somewhere that actors are prostitutes, what does that mean?

You mustn’t understand that sexually, but as it was understood in eighteenth-century France: actors were considered prostitutes because they felt real emotions, which they ranted about in public, and because their bodies were the tools they used to do their work. That’s not a moral judgement, it’s a fact. They’re not simulating anything, so it’s prostitution. But it’s a sacred kind of prostitution, prostitution for art. There will always be bad faith assholes who say, “Breillat said actors are prostitutes” But who wouldn’t want to be prostituted for art?

You say that as a filmmaker, you are tied to a “pornographic imperative.” What is that?

Since every filmmaker just gives up, since they delegate what’s most beautiful about ourselves—namely, sexuality—to pornographic cinema, I have to take care of it. The imperative is to say: “No, that’s not the way you make love.” It’s showing that the filmmaker’s gaze transcends all of that, that it isn’t about pornography, that something else entirely is going on.

Your cinema is constructed on this tilt between the clothed world and the unclothed world.

Yes, that fascinates me. When there used to be absolute sexual freedom, after the pill and abortion, before AIDS. In that era, you could go with any guy you wanted, and it could end badly, you could be murdered. I always kept myself from doing that, I was afraid, but I think that I would have followed any Jack the Ripper. That could be fascinating.

DETAIL FROM BOTTICELLI, VENUS AND MARS (1538)

Beauty and the Beast is very you. How did you want to film it?1

Catherine Breillat’s Beauty and the Beast was never made: conceived as the third part of a fairy-tale trilogy—following Bluebeard (2009) and The Sleeping Beauty (2010)—it was a project developed by the director but left unreleased, of which only traces remain in her statements (Filmmaker Magazine).

It is the subject for me. No one has ever talked about or filmed what’s really interesting in that fairy tale, that’s why it’s my subject. What needs to be said is that in reality, the Beast is the prince: we see him as a beast, but he is Prince Charming. The Beast is the dark object of desire in some way. It’s the sexual attraction that you don’t want to admit, so it takes the form of a beast to which the Beauty is very attracted. I’m the only one who can say that, the others are kitsch, except for Cocteau, who is obviously sublime.

The madness of filmmakers seems really tied to a denial of the real that’s very strong, a way of bucking it, of forcing it open.

Saying that you're making a film is already a refusal of the real. You don’t have a penny to make it with, but you have to tell yourself you’re going to make it so that you can raise the money—just barely, but you end up raising it. You have to refuse the real in order to make films that aren’t made for the market. If you want to make a product for the market and use “bankable” actors that are pushed on you by the big agencies, and television producers give you money… then you’re not in denial of the real.

What kind of painting matters the most to you?

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I adore Raphael. Actually, I love them all: Titian, Botticelli. I borrowed their soul, since the soul is what counts. I have this thing about the eyelid that comes from quattrocento. That kind of transparency, it’s like Mona Lisa’s smile, but with the eyelid. There is very little flesh in those paintings, but what flesh there is is incandescent. It’s sublime because it’s sublimated. It’s a very particular type of light that materializes like a screen, and the face has to spread out over the screen, which creates a kind of vertigo. Painters position the irises of the eyes in a certain way, and that’s not something the actors can know. I’m the one who has to say, “No, cast your eye downward.” That detail changes the entire meaning of the scene. Painting, after all, has a kind of écriture that’s embedded in our minds. Basically, I consider myself to be a painter.

DETAIL FROM LORENZO LOTTO, PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN (1510)

Catherine Breillat is a filmmaker and writer based in Paris. She is known not only for her films focusing on themes of sexuality but also for her best-selling novels.

Murielle Joudet is a film critic for Le Monde, as well as for TV and radio. She is the author of Isabelle Huppert: Vivre ne nous regarde pas (2018), Gena Rowlands: On aurait dû dormir (2020), and La Seconde Femme: Ce que les actrices font à la vieillesse (2022).

finanziato dall'Unione Europea - Next Generation EU