Paradessence in Los Angeles

“You must reduce everything to its most brutal contradiction.” That’s the single most important piece of branding advice I’ve ever received, from my old mentor Michael Rock, paraphrasing Rem Koolhaas. Lately I’ve been thinking about and repeating this advice more than ever. It’s the only thing I can think about as I stare into the void—the one at the heart of so-called brand culture. Brand culture is all around us, and it feels like something but is in fact nothing. Yet nothing has a shape, a texture, a structure. And the structure is the brutal contradiction itself. I like the advice because it’s a simple dictum, something to follow, abstract but also actionable. All of a sudden there is a sauce to reduce. A way to process the thickness of our reality. Thick and insubstantial at once—get it?

I first heard about the brutal contradiction in the boardroom, and it was funny because it had that kind of droning European truth to it, humorous but also not. I instantly loved the concept on its own terms, and I also loved the way it encapsulated another thing I knew, the idea of paradessence, a concept from a strange book about trend forecasters, Alex Shakar’s 2001 novel The Savage Girl. In that book, fictional marketers celebrate the paradoxical essence at the heart of every good marketing concept. The paradessence is the “schismatic core” or “broken soul” of every consumer product. For example, coffee is both energizing and relaxing. Ice cream connotes both eroticism and innocence—in the view of the book, it’s at once semen and mother’s milk.

I sit here in Los Angeles nursing my baby and reading a book about the prophecy of the end. It says we only have about 1,300 years left on Earth, because an asteroid is going to hit the planet and wipe out human life. But before that, very soon in fact, a new species is going to be born to humans, called the Rave Children. These children will appear disabled, but will actually have the ability to form telepathic pods called pentas, which will be a whole new kind of intelligence and power. Milk drips from the corner of my baby’s mouth as I take in this information. Is what I’m reading transmittable via breast milk to my child? Other kinds of spooky information are. How can I give her antibodies automatically and in anticipation of an illness, still in the future, but not this knowledge? I look out the window and ask the blue sky dotted with palm trees to tell me what transmits, what is possible, what counts as information and what doesn’t. The book explains how the Rave Children will be born, link up in the collective intelligence pods, and not need us. As a prophecy, it’s not unlike the prophecies of Octavia Butler, who wrote future histories of a brutal, burning, telepathic Los Angeles.

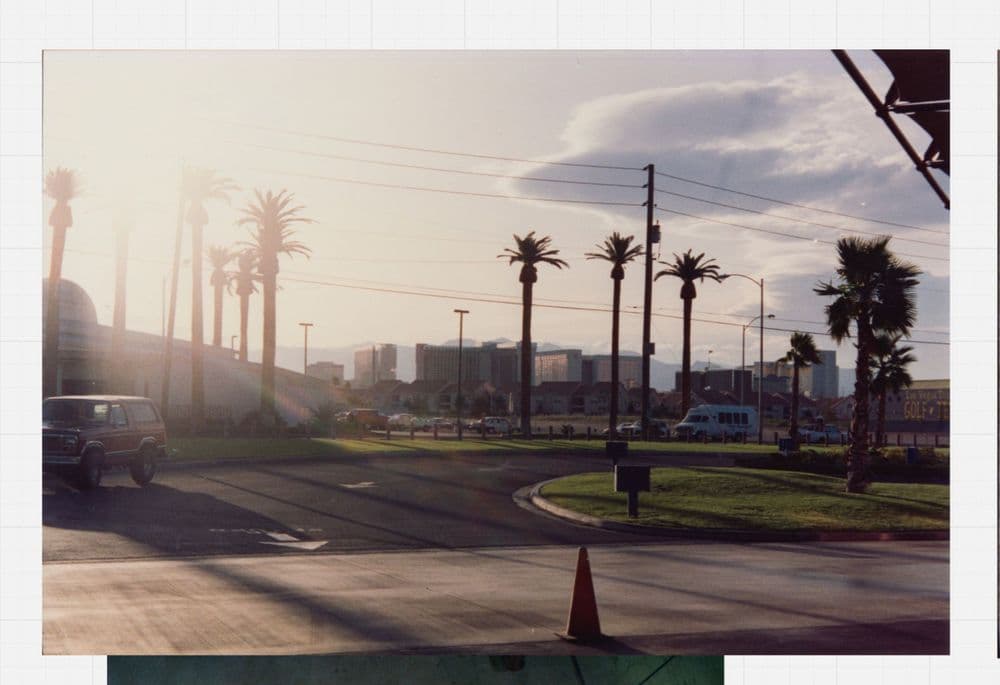

I was enchanted when I first moved here. While flat on my back in bed, I could see a sliver of the moon and a smattering of stars and a swaying bunch of palm trees outside the window. Now, in my new apartment, I see even more. And then I learned that the trees’ time is limited, and I was shocked. Each palm tree will last a hundred to a hundred and twenty years and then fall, never to be replaced. Our image of the city is highly temporary. It’s expiring as I type. But it’s in these photographs; it’s here, outside my window; and it’s in our collective consciousness of LA.

Branding is about collective consciousness. The idea that you’re creating the sum total of what people think about something, this impossible idea. For this reason, branding is very much connected to being stoned as a teenager. Stoned teens are always marveling to themselves, imagining what would happen if they really knew what other people were thinking. What if I could think what they think, just for a moment? What if I was telepathic? Professional branding, my vocation, attenuates this possibility, draws it out. Let us elaborate on that for you…

I nurse my baby and I write this text and I look out at the blue sky dotted with palm trees and I keep winding around this point I want to make about friction and authenticity and deep contradiction and brand culture. Let me try again.

A colleague was on my screen the other day, talking about the entitlement of the consumer, how everyone now wants the thing they see on their phone, right then and there, not caring whether the thing is real, or good, or authentic. I nodded along, eyeing my fake designer flats on the floor beside me. Nasty white vinyl, already smeared with mud. But I make them work. If I was at a different point in my life, I would feel compelled to make sure they were real. In Berlin, I was paranoid about acquiring cheap, shitty things. Now in LA I don’t care anymore. I order them and I go on my merry way. The consumer isn’t an idiot, she’s your wife, David Ogilvy is saying in my mind. She’s not entitled, she’s bearing the contradictions of the marketplace.

The thing about feeling entitled to the dupe of a luxury item—and here we’re talking about a luxury item with some deep design provenance, something steeped in craft and culture and origin—the thing about feeling so entitled to that thing that you just click “order now” and buy its crappy vinyl dupe and then wear it and feel no shame—the thing about that phenomenon, in which I participate, is that it speaks to the brutal contradiction of consumer desire. It is a phenomenon in which I am both a producer (of branded meanings) and a consumer (of crappy dupes). You are supposed to desperately want the thing. You are supposed to feel incomplete without the thing. You are supposed to see the thing and be rendered suddenly naked, feel that your current presentation is off-kilter and not up to snuff. You are supposed to feel this deeply and intensely, and be motivated by it (economically, personally). And then at the same time, you are supposed to have restraint and integrity. You’re meant to be easily manipulated, bowled over by what you see, quote-unquote inspired, and then instead of finding the cheapest, easiest puzzle piece to fill that void, you’re supposed to believe that the expensive, rare, brand-name version is what will really complete you properly. You’re supposed to save up, forgo other things, organize yourself, and get the original, “good” thing, not the crappy, cheap, available, more or less identical thing. And this is a brutal contradiction. You’re supposed to desperately want the thing and then wait for the real, good thing. Whether or not you can afford it. Whether or not it makes sense.

This whole stream of thought is a long introduction to one of my favorite nuggets of brand ephemera, regarding the thing that ties together the truth of brand culture and the truth of LA. The Bling Ring were teenagers who ripped off celebrities in Los Angeles in the 2000s. They stole hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of clothes, accessories, drugs, and other stuff from celebs. And here’s the thing: In doing so, they struck right at the core of the brutal contradictions of marketing. This is how one of their lawyers put it: “These kids went on shopping sprees. . . . It’s like they went shopping online. They’d look at a picture on some website of a celebrity holding a Marc Jacobs bag, and they’d say, instead of going to a Marc Jacobs store and getting a bag like that, I want that bag that Lindsay is carrying—I want Lindsay’s Marc Jacobs bag.” And then they’d go to her house, break in, and get that exact bag.

They saw through the brutal contradiction of the marketing message. They were supposed to desperately want the thing, to need to bring it into their real lives so as to create intimacy with the object. And they were also supposed to understand that that meant a similar object, not that exact one. They were meant to find something that looked exactly the same, save up for it, purchase it. They were meant to flip so many burgers to get this bag, flung casually over the wrist of the celebrity. They were meant to want the bag, but not that exact bag. You’re supposed to see the image in the magazine and save your pennies, not commit crimes. And that is the brutal contradiction at its core. The proximity and the double-mindedness at the heart of this city. The wind is ruffling the palm trees as I write this. My shoes are fake. My heart is real. I’m here.

Emily Segal is a writer, strategist and trend forecaster based in Los Angeles. She founded the consultancy Nemesis and the trend forecasting group K-HOLE. Her debut novel, Mercury Retrograde (Deluge Books, 2020) was a New York Times New and Notable Book.

All images courtesy Archivio Slam Jam.

finanziato dall'Unione Europea - Next Generation EU