The Density of an Hour

Jiajia Zhang's practice revolves around the private and the public, and the ways we divide space to create the two. Her recent exhibition at Cordova in Barcelona explored the fragmented nature of time—a theme that resonated with writer and researcher Aurelia Guo, author of World of Interiors (2022), who is writing part of the script for Zhang's forthcoming film Tables, Doors, Songs. In her writing, Guo incorporates research, life-writing, collage and appropriation. "I write about economic cycles of wealth and poverty," Guo explains, "as well as about migrants, tourists, and refugees." In their conversation, the two artists found common ground in these fragmentary approaches, discussing how such techniques capture experiences of time and space across China, Switzerland, New York, and London. Zhang took all the photographs that accompany this article in Shanghai, where she was filming her latest project.

When I began my film project Tables, Doors, Songs—still a working title—I was newly pregnant. As the project evolved, and especially after my daughter's birth, my sense of time shifted completely. It became a new architecture layered over everything else: breastfeeding time, fragmented work time organized around her schedule. My first solo exhibition took place when she was seven months old; time was literally cut into pieces.

You used time and clocks throughout the exhibition, Duty Free at Cordova in Barcelona—from the disjointed opening hours on the door to the motif of wall clock packaging mounted on the ceiling of one of the rooms. Time is a pressing dimension in many of the images you've shared from the film project too. It's palpable in the elderly parents at the marriage market in the park, in their expectations of their children, and their succession by future generations. People's Square—a horse-racing track before 1949—is now a wedding market where parents gather every weekend to find partners for their children. It's incredible that it used to be a racetrack. I reflected on horses in World of Interiors as strong creatures that are also "prey animals" dependent on flight for survival. The racetrack makes time a quantifiable measure of success and failure in a very explicit way.

While filming in Shanghai, I stayed on the city's periphery in an almost empty, barely furnished apartment. The isolation was striking—gated communities stretched along the highway, far from the city's vibrant center. In contrast, the glittering core of Shanghai projects an illusion of connection to the wider world, but returning to the outskirts reveals a different reality: a vast urban sprawl where density coexists with profound alienation. That experience made me newly aware of the tension between center and periphery, and how these shifting geographies shape both belonging and dislocation.

The journeys between the outskirts and the city's glittering center were carried by migrant drivers, many living in precarious legal and economic situations. As a tiny film crew—just me, my partner behind the camera, and our daughter, who sometimes appears in the film—we often found ourselves in quiet proximity to their lives. In the car, we'd overhear phone calls: drivers saying goodnight to children they hadn't seen for months, asking about homework, making quick, tender check-ins across distance.

Some shared their stories with us—former fashion designers, workers who had lived under restrictive contracts in Japan, people who had only recently arrived in Shanghai. Many didn't know the streets well, not only because the cityscape changes so rapidly, with roads constantly renamed, but also because they were new to this immense sprawl. Their lives seemed defined by stretched and compressed time: fourteen-hour shifts that left them nodding off while driving, trying to earn enough to return home, even briefly. These movements between periphery and center, carried by those whose lives are suspended between places, became a quiet thread in how I experienced and filmed the city.

I've had similar experiences staying with my cousin in Shanghai. She's the only one in my extended family who migrated internally—from Harbin to Shanghai—her father is Shanghainese. She bought her apartment after seeing it advertised on TV, before it was built, and it came fully furnished. She told me that the apartments throughout the block were identical inside and out. I was fascinated by the chandeliers, mirrored surfaces, walk-in closets, and other features I associated with the reality television I was watching at the time—syndicated American shows broadcast in Australia in the 2000s.

Your comments also made me think of how city centers attract so many people, including those who remain marginal or vulnerable and who rarely become central figures later on—whether in finance, commerce, or the cultural industries of fashion, publishing, or art. There's something about a moving car that enables conversations that wouldn't happen elsewhere. Cars can also carry you seamlessly across zones of legality and illegality—to peripheral markets where pirated DVDs or counterfeit bags are sold by people who may or may not have proper documentation or work rights. They don't have corner offices in skyscrapers.

It reminds me of my relationship to Harbin, which I made the center of an essay in my book World of Interiors. It's a peripheral, provincial city, yet home to more than ten million people. It's existed as a city only since the late nineteenth century—just a few generations in one family's history, not that mine has necessarily been there from the beginning.

Buying apartments carries enormous weight in Asian societies, especially in China. It signifies adulthood and status, but it also brings crushing pressure—a desperate drive to live a "normal" life. I felt this pressure from my Shanghai family, navigating their ideas of what life should mean, though my thoughts were elsewhere.

For years I pushed these expectations aside, postponing motherhood until my early forties, when I finally had my daughter. I don't know how my life would have unfolded had I stayed in China. In Switzerland, I began learning a new language, and through that process—fragmentary, built word by word—I started collecting other fragments: texts from libraries, magazine clippings, images, and conversations. Slowly, they gave shape to a different understanding of myself, one not defined by my parents' expectations.

They valued mathematics and science, while I was drawn to language, literature, and images. We compromised: I studied architecture at ETH Zürich. Architecture training starts extreme—scheduled until five, but the first night you're there until midnight, continuing throughout seven years of education. You're constantly pushed to extremes of what you can deliver. Many workplaces use this to extract maximum from people through internships and other exploitation-prone models with little regulation or resistance. It becomes normalized. During those years, my parents moved back to Shanghai, which unexpectedly gave me space to breathe. Growing up I felt claustrophobic, but now they visit once a year, mostly to see my child.

Switzerland holds a duality for me—both constraint and liberation. It taught me that reality isn't fixed, that identities, like languages, can be pieced together and reassembled. It offered freedom, yet remained a blank space—quiet, measured, a middle ground without extremes.

I spent a short time near Zürich as an undergraduate, when I was dating a Swiss exchange student studying engineering at ETH. I learned a little about the Swiss education system—its class stratification, even within engineering as a profession.

But I can't help connecting your experience to the history of Chinese labor migration and anti-Chinese racism: the perception of East Asians as robotic drones good at math, impervious to 80-hour work weeks—uncreative, uncritical, apolitical—and the pressure to conform to those expectations. Many of the ideas have stayed the same since the era of railroads, from the mid-nineteenth century onward.

I've come to see the Chinese, French, German, and Australian education systems from a wider perspective. Parents' emphasis on education was meant to bring social mobility—it did in a roundabout way in my case—but these systems are not meritocratic. Every education system entrenches inequality. Now, in the UK, professions like law, medicine, and architecture are in decline: despite years of training, people end up underpaid and exploited. Privilege and power give people more scope to be less socially conforming—to pursue arts careers, queer identities, or radical politics. Survival can mean giving up a lot, as it does for migrant workers driving taxis in Shanghai.

In architecture school we worked through renderings and collages—assembling images from fragments. Embedded in those visions were ideas about class and about what a "good life" might look like. That process has stayed with me, shaping how I think but also making me more critical of images—more suspicious of how they construct realities that can be both seductive and hollow.

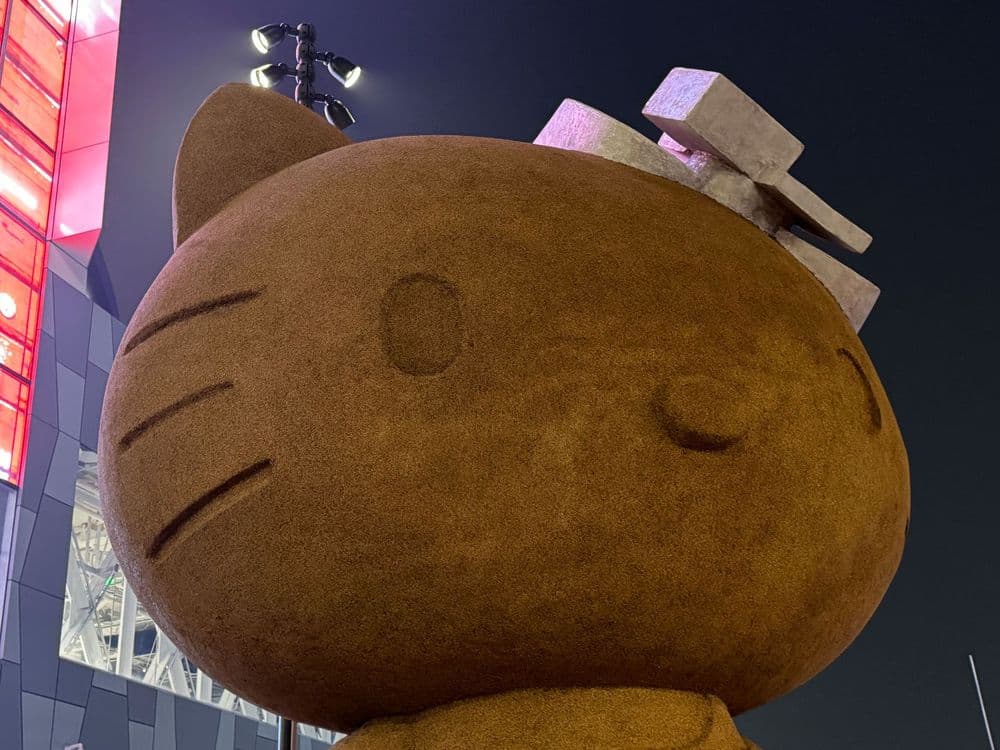

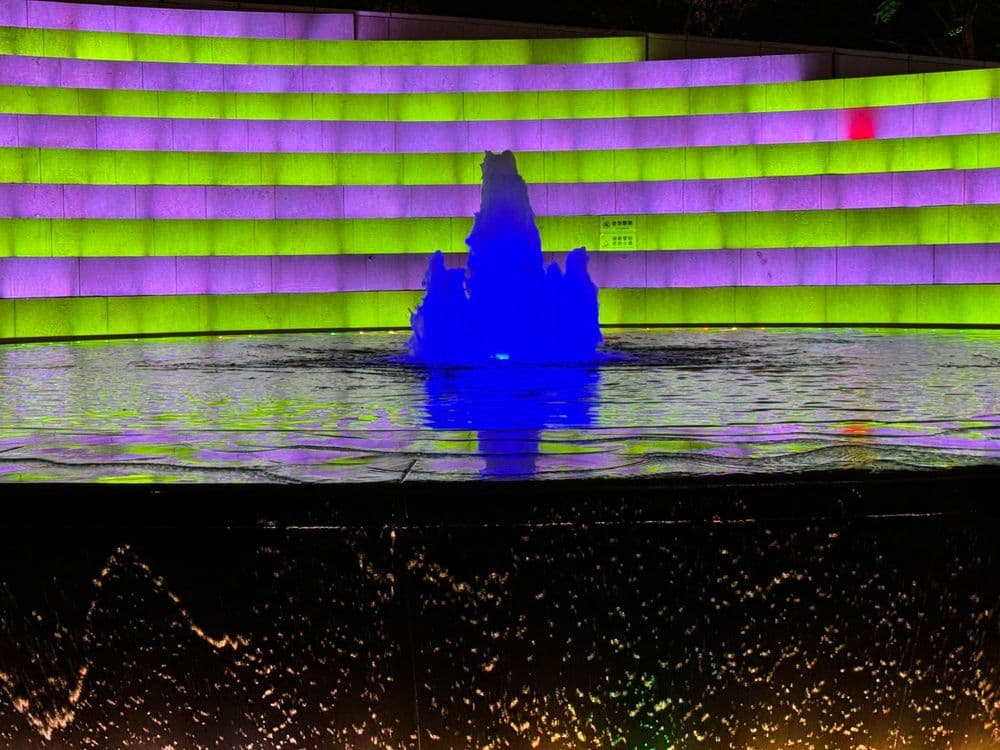

I think of Shanghai's skyscrapers this way: during the day they seem almost dull, stripped of vitality, but at night, under layers of light, they transform into something between reality and fiction—projections of desire and aspiration. This act of assembling fragments into a provisional whole connects to my working method, and to what I also recognize in your practice. The world is pieced together from fragments, and identity, too, emerges through this ongoing layering.

It makes sense that many of the buildings you showed me began as computer-generated images—and they still look computer-generated. Yet they exist on earth. They're exposed to the built and natural environments—smog, smoke, rain, humidity—and we perceive them in their context and ours. That makes them sites of memory, fantasy, and other forms of human meaning-making.

A New York artist-filmmaker at Art Week called Shanghai's architecture ugly. He's both right and wrong. Much of the skyline speaks the global language of glass and malls—a kind of aesthetic that overwrites local histories. Many buildings are indeed bland, rushed into being, built for profit rather than memory, often borrowing styles without understanding them.

And yet, I want to defend them—perhaps because I've seen the labor behind them: workers hauling steel and glass in summer heat, families buying these apartments and making them their own, filling them with small dreams and personal histories.

But a city built too faithfully on a textbook of how a "modern" city should look carries danger. It risks flattening itself, erasing memory, sweeping away existing structures and communities—something I've witnessed in Shanghai, where people are displaced at dizzying speed. It reminds me of those videos imagining Gaza's "future," full of glass hotels, perfect promenades, luxury towers—the same architectural script projected with violence, a future built on deliberate forgetting.

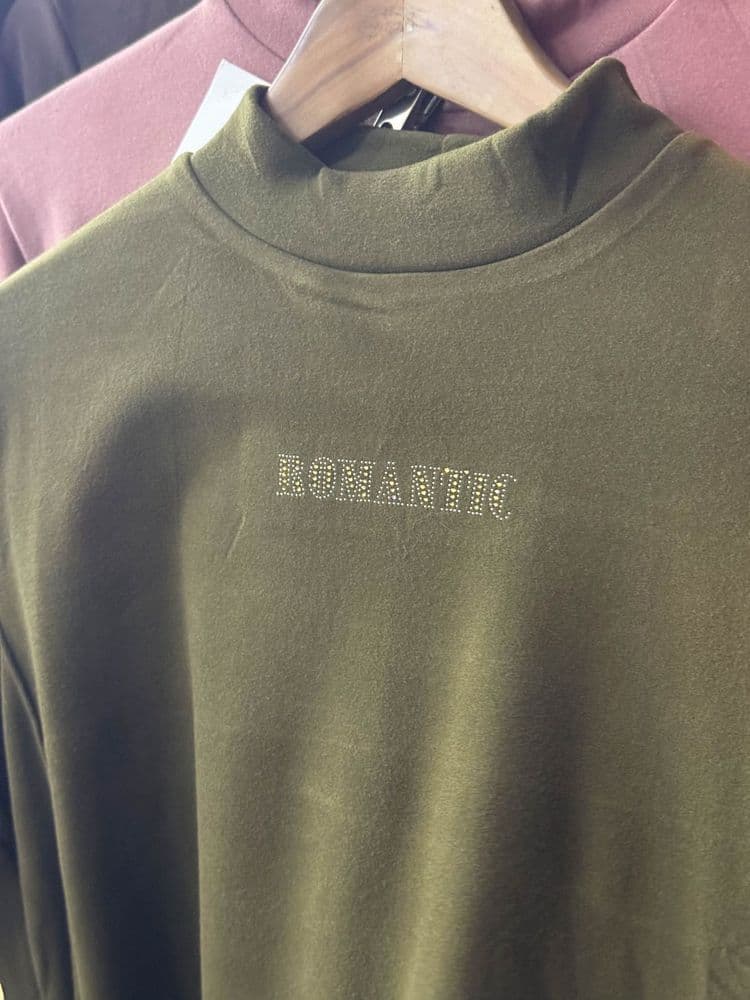

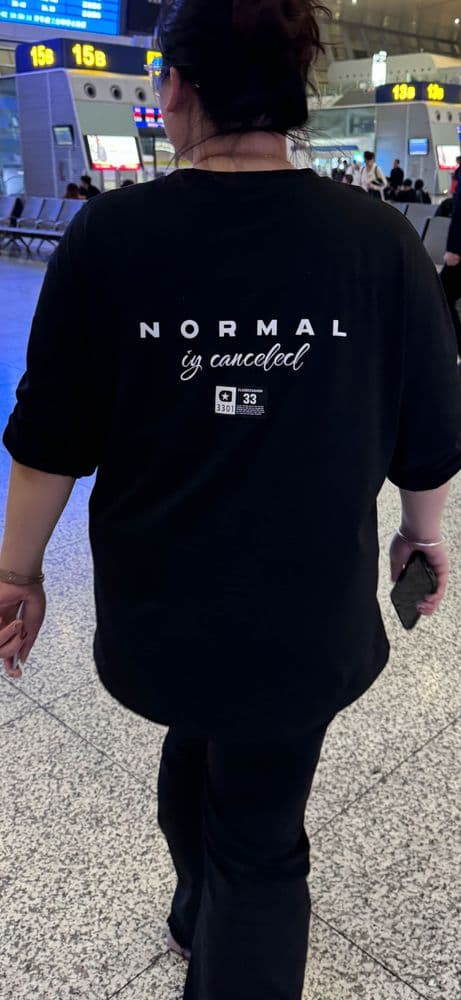

There's also something in Shanghai's restless aspiration, its reaching toward a Western idea of modernity. The buildings wear that longing openly; they resemble mistranslated T-shirts with mismatched slogans and wrong words—clumsy, strange, and somehow poetic in their ruptures. You can see a city mid-sentence, trying to catch up, trying to belong.

Aurelia Guo is a writer and researcher based in London. Her most recent book is World of Interiors (Divided, 2022). She is a Lecturer in Law at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Jiajia Zhang works across digital (moving-)image media, video, and photography, presented through spatial installations. She rearranges both self-produced and found visual material in precise constellations, relating fragments in unexpected ways. In doing so, social phenomena and mass-produced products meet minor details like private YouTube videos or Instagram posts. The artist opens a charged borderland that blends the personal and the generic, challenging entrenched definitions of the private and the public. On one hand, her work offers a visual inventory of reality; on the other, it confronts us with the speculative element inherent in perception itself. Jiajia Zhang studied architecture at ETH Zürich (2001–2007) and photography at the International Center of Photography, New York (2007–2008). In 2020, she completed an MFA at the Zürich University of the Arts (ZHdK). Her work has been shown at Milieu, Bern; Cordova, Barcelona; Istituto Svizzero, Milan (2024); Nottingham Contemporary, Nottingham (2024); Giorno Poetry Systems, New York (2024); All Stars, Lausanne (2023); Kunstmuseum St. Gallen (2023); Kunstraum Riehen, Basel (2023); Fluentum, Berlin (2022); Swiss Art Awards, Basel (2025, 2022); FriArt, Fribourg (2022); Coalmine Gallery, Winterthur (2021); Kunsthaus Glarus (2021); Fondation d'entreprise Pernod Ricard, Paris (2021); Haus Wien (2020); Kunsthalle Zürich (2020); and Kunsthalle St. Gallen (2019).

finanziato dall'Unione Europea - Next Generation EU