We will Remember: Salvo and Leonardo Sciascia

There they are, Salvo and Sciascia, in the back seat of a taxi on the Lungotevere, facing Castel Sant’Angelo. This late afternoon in autumn 1988 is unusually warm, and the taxi driver—perhaps due to the proximity of the Vatican, or perhaps because he had hit a couple of green lights in a row—is silent. The silence and the pleasant air from the lowered windows entice the forty-one-year-old artist and the sixty-seven-year-old writer to untether their thoughts and follow them from a distance, curious to discover where they might end up, without really caring.

We, however, are curious, and we hypothesize.

Salvo takes out a pack of cigarettes and offers one to Sciascia, who accepts with a smile. Salvo lights it for him before lighting his own. He takes a long drag and observes the effects of the sunset on Hadrian’s mausoleum: the oranges that fade to red on those ancient stones, the angel at the top whose bluish gray shifts from azure to pink. He thinks of Sicily, of the sunsets of his childhood on the hills of Leonforte. The light was the same, yet different, like water from a spring adapting to different outlets. The opposite of that documentary about the journey through Italy with Andrei Tarkovsky and Tonino Guerra, where the self-exiled Russian director wasn’t struck by monuments, squares, or cathedrals, but by plowed fields, by tilled earth, because it’s the same in Italy as in Russia. Perhaps beauty is being able to recognize the familiar in different places, to grasp uniqueness in repetition. Like children who repeatedly watch the same cartoon or want to hear the same story until exhaustion. Training oneself to perceive wonder, to find treasure with every step, to recognize it as such without needing the treasure map from Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel.

Sciascia inhales from the offered cigarette, studies its ember, then seeks the same vibrant orange on the stones of Castel Sant’Angelo, and isn’t surprised to identify it without seeing it. Five years earlier, he was diagnosed with a myeloma that blurs his vision, so he has grown accustomed to looking more with his imagination than with his eyes. Perhaps this is why, over time, his interest in art has focused on engraving, a medium both cultured and popular. Dual in that it stems from a matrix engraved in a mirror-like manner, which must be worked in reverse to produce legible multiples. Perhaps this inverted mystery is what connects it to his writing. Or perhaps because it produces concrete images made of grooves and reliefs, perceptible to the touch, even in the dark, without looking. That day, however, he thinks of the Vatican and the Apostolic Library. Or, rather, the library archives. There is no better strategy to hide certain treasures than to display some others prominently. Of some treasures, only the map exists, the suppositions. Certainly not the immediacy, sincerity, and adventure of childhood: the X on the map of that perfect book, where treasure isn’t deception, but the engine of journeys, of joy, of life. (I must reread Stevenson.)

It’s not misguided to imagine that two seemingly distant people, but having a deep, intense affinity, would think of the same things when facing a landscape, mounting different trails of thought only to land at the same crossroads, on the same X. What is the nature of their affinity? Why do they like each other? Certainly, they are both Sicilian and both love books. Sciascia’s writing and Salvo’s painting manifest a shared sensibility. Their images, their stories, don’t describe, but suggest. They’re built to be completed. They often arise from a factual situation, which they then use to speak of other things. They introduce elements that at first might seem extraneous and that require time to be assimilated. Sciascia uses the format of detective fiction to talk about the Mafia and the multiple faces of power; Salvo’s subjects are, for the most part, pretexts for painting.

In Todo modo, the nameless protagonist, a painter, at one point finds himself pondering a pair of glasses, a key object in the plot, thinking of them in both painterly terms—those worn by the saint in Rutilio Manetti’s painting Saint Anthony Abbot Speaking with the Devil—and literary terms—as in Spinoza’s trade, or Anna Maria Ortese’s story “A Pair of Glasses”. “And here at this moment, as I write, the fact of remembering these images (actual images and images from words) surprises me and adds disquiet to disquiet.” The character moves between retinal vision and mental vision to bring reality into focus, and his disquiet emerges from a world made of multiple irreconcilable focal points.

⠀

Salvo and Sciascia first met in person in April 1987, on the occasion of an exhibition curated by Sciascia and Daniela Palazzoli at the Mole Antonelliana, Unknown to Myself: Portraits of Writers from Edgar Allan Poe to Jorge Luis Borges, but they had been writing to each other for a few months already.

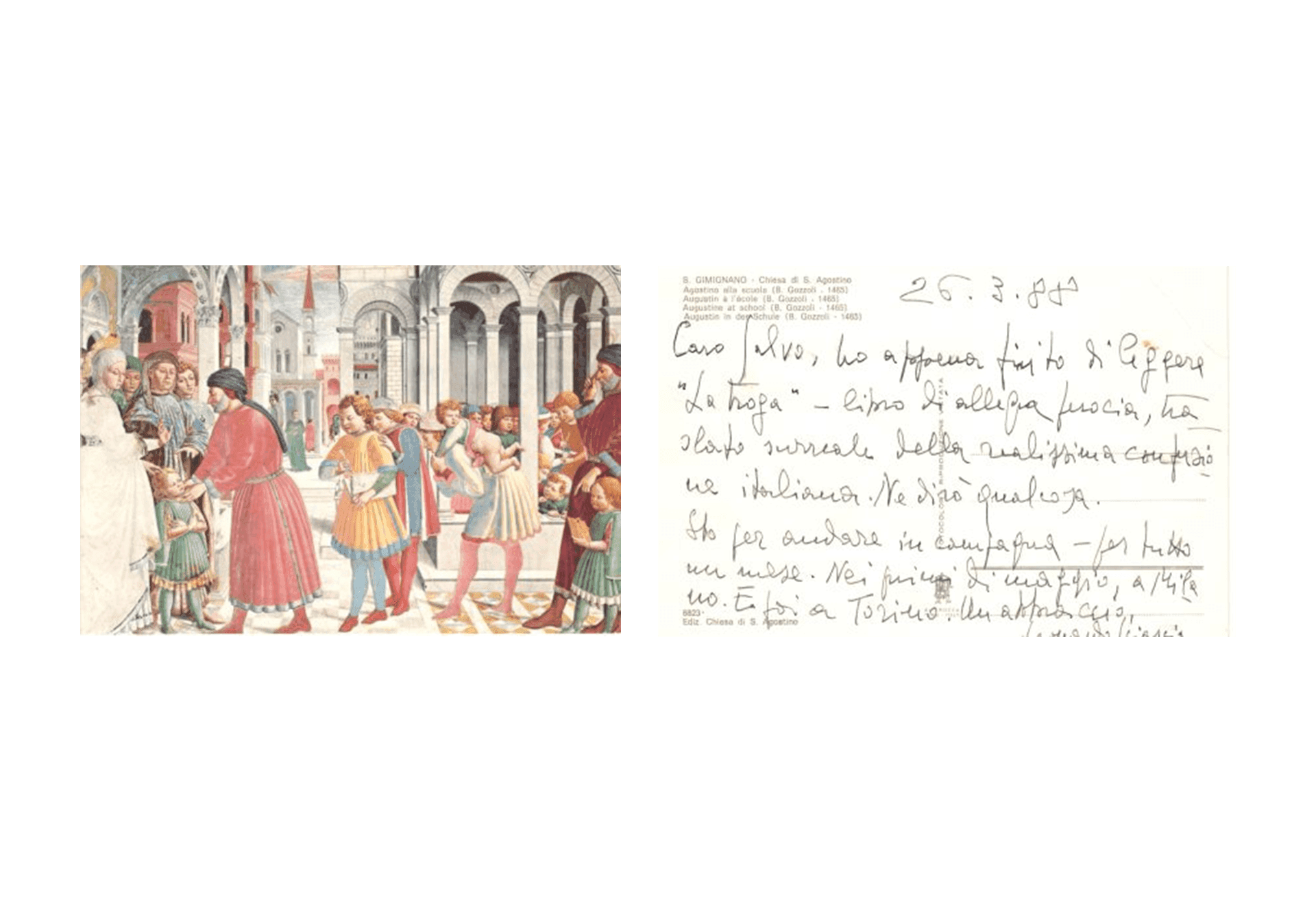

On March 5, 1987, Sciascia to Salvo:

«I’ll come to Turin on April 8 for the opening of the exhibition of photographs of writers. Having suggested it and written the preface to the catalogue, I’m obliged to be present (which weighs on me not a little, now accustomed to solitude, or almost). I hope to meet you».

And again, on March 24:

«I’ll arrive in Turin on the morning of the 8th, for the opening of the exhibition, at 11:30 (I don’t know where it’s being held)».

In the halls under the dome of the Mole Antonelliana, after meeting Salvo for the first time, Sciascia gives a brief introduction to the theme of the exhibition:

“A man who dies tragically at thirty-five is, at each point in his life, a man who will die tragically at thirty-five. In a few dry words, this is what Goethe called entelechy, a concept on which this exhibition of photographic portraits of writers has been built. With photography, life is captured and understood in a frozen moment, made eternal, with which the essence of the subject represented is identified. The present of when the photograph was taken, the future that has become past, that whole which death has concluded. A spell of contraction of time, caught at the point of dissolution and oblivion, and precisely for this reason invested with an extreme brilliance. Nothing is closer to the abolition of time, and simultaneously nothing is further from it, than photography—a humble and daily war against time which in its violent and invasive ubiquity reaches and surpasses other forms of war against time, namely history and the novel.“

Shortly after, Salvo approaches and asks, “Mr. Sciascia, may I offer a consideration?” “Please, and call me by my first name.” “Thank you. It seems to me that your thesis on photography implies the verified death of the subjects portrayed.” “Yes indeed, in the exhibition we selected only photos of dead writers.” “Well, with all due respect, there may have been an oversight in the selection. I understand that Erskine Caldwell is still alive and well.” “Technically what you say is true, but Caldwell, being a great gentleman, to avoid disrupting the theoretical structure of the exhibition, did us the great favor of dying just yesterday afternoon.” The few people present at this exchange remain somewhere between indignant and petrified (life is made of small solitudes, as Roland Barthes reminds us in Camera Lucida [1980], to stay on the theme of photography), while Salvo and Sciascia have a laugh and go for coffee.

After that first meeting, the tone of the letters changes, and the relationship between the two evolves from an exchange of information on common interests into a tender friendship.

Salvo, May 2, 1987:

«Dear Sciascia, I hope your health is good enough to allow you to work happily (I’m using the familiar form with you, but only after overcoming strong resistance). Who knows if we’ll have the chance to see each other again. I hope so. Meanwhile, to seal our happy meeting, I’m sending you (hoping it doesn’t embarrass you and that you like it) an etching, a unique copy, made especially for you. I’m also enclosing the plate».

Sciascia, May 15, 1987:

«Dear Salvo, returning from the countryside—an unpleasant stay, both for the weather and for my ailments—I find your letter and the things you’ve so affectionately sent me. I’ll hold the etching very dear, and the small plate (I have some from the eighteenth century, images of saints): an Arab-Sicilian synthesis. You’ve understood that etching is the form of expression I most understand and love. I’ve collected so many sheets in my life that I no longer have the strength and time to review or organize them. I don’t have much sensitivity for color, very few paintings around me. I therefore feel more confident in telling you that your drawings are beautiful, intense».

Salvo, September 1987:

«Dear Sciascia, it’s horrible to need doctors; certainly one can reach the point of wanting it. In this case, you’ll have the best at your disposal and everything will be resolved in the best way. However, I persist in wishing that nature will provide to halt the progress of the illness. If and when you come north, know that I’ll be happy to meet you in your free time, even in Milan, where I often go, having my main dealers there. And if I come to Sicily, the hope of seeing you for a few minutes will be my first thought».

Sciascia, August 2, 1987:

«I’m staying in the countryside, writing, as usual, the little book of every summer. And I read too, but very little. My eyesight is declining more and more. As soon as I’ve finished writing the book, I’ll come north, hoping that at least the decline will stop. . . . From the catalog you’ve now sent me, I understand your painting more, and better, but I always desire to see paintings themselves, not reproduced».

Sciascia, September 22, 1987:

«In Milan, I always stay at the Manzoni hotel on Via Santo Spirito. I’ve asked the ophthalmologist Brancato, our fellow countryman, considered among the most expert in laser matters, for an appointment. . . . We’ll see (it’s appropriate to use the verb see with hope). But I plan, at least for one day, to come to Turin to tour the bookstores in your company».

Salvo, February 2, 1988:

«Dearest Sciascia! Here are the reasons why I’m writing to you only now: Discretion demanded (against my desire) that a few days pass since our meeting in Milan (a happy meeting, for me, from the memory of which I draw continuous teachings). . . . Moreover, I had to wait for the little painting I made for you to dry. I hope you’ll like it. . . . And speaking of books, will you forgive me if I say a few words about yours? I consider it one of your best. Even though your “average” has always been extraordinarily high, this new one, written more for the future than for the present, has a lightness that reminds me of clouds. Melancholic too, but as a colorful twilight can be. Complex in its meanings so as to allow and want different readings. And the confirmation of achieving what Sa’di calls “the inaccessible simplicity”».

Sciascia, February 12, 1988:

«Dear Salvo, I’m pleased to have news from you, and pleased with the gift. It sits before me, leaning against some books, this Sicilian twilight of which one can also say it has “inaccessible simplicity”—an expression I like very much».

Salvo, April 5, 1988:

«Dear Sciascia, I imagine you in a green oasis, with some patches of pink from flowering trees. . . . When you’re in Milan, I’ll try to find you and if you haven’t committed to others, I’d be happy to accompany you from there to Turin (in my beautiful new Mercedes that makes my “colleagues” so jealous), where I hope we can spend some time together and, maybe if it’s a nice day, show you some beautiful corners of the region».

Salvo, July 1, 1988:

«Sciascia! My dearest friend (can I say so? or is a mirage making me say it?). . . . I was sorry, but only a little, not to have been able to show you my books and a two-meter painting that I had wanted to finish before your arrival: a sunset where everything is suffused with red (a red pursued, truly, for ten years) as, in reality, but rarely seen between the end of summer and early autumn».

Sciascia, July 4, 1988:

«Dear Salvo, how are you? I’m getting worse, and only those two or three hours I devote to writing give me a little relief—only that my eyes, at a certain point, force me to stop».

⠀

Salvo, September 12, 1988:

«Dear Sciascia, dearest Leonardo, . . . In autumn, in winter, apart from a visit—I fear inevitable—to Paris to attend an exhibition of mine, I should go to Rome, where 2RC, which produced Guttuso’s graphics, is urging me to sign a rather flattering contract. By any chance, will you be going to Rome? I could make my visit coincide with yours, and if not, I could “jump” to Sicily (my heart’s voice), where having a coffee together and chatting for half an hour would make the journey light and easy».

The taxi continues through the streets of Rome, leafing through in its wake years made of painted trees and trees transformed into paper, pages of books and pages of letters, apprehensions, gifts, expectations. At dusk, the car stops in front of Sciascia’s hotel. The writer gets out, looks around, searches for something in the sky, then looks at his friend and, absent-mindedly, says, “We will remember this planet.” Salvo smiles, looks at the ground, then looks at Sciascia, serious, and asks: “Pascal?” Sciascia laughs, raises his eyebrows a little, and, oscillating his hand, replies: “No, almost. But we’re close.”

Shortly after their last meeting, Adelphi publishes The Knight and Death (1988). The protagonist is a commissioner afflicted with a serious illness investigating the murder of a lawyer. In one passage, Sciascia has him say, “Treasure Island—a reading, someone had said, that was as close as one could get to happiness. He thought: I’ll reread it tonight. But he had a precise memory of it, having reread it so many times in that old and ugly edition once given to him. He had lost so many books in his moves from one city to another, from one house to another, but not this one.”

A year after the book’s release, the phrase “We Will Remember This Planet”—a quote from Auguste Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, the French symbolist who was a friend of Stéphane Mallarmé—is engraved as an epitaph on Leonardo Sciascia’s tomb in the cemetery of Racalmuto.

We would like to thank Archivio Salvo for their invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article and for providing the images reproduced herein.

Matteo Mottin is co-founder and curator of the art project Treti Galaxie. He writes regularly for Il Giornale dell'Arte.

Born in Leonforte (Enna, Italy) in 1947, Salvo moved to Turin in 1956. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, he became part of the city’s artistic scene, forming connections with figures such as Alighiero Boetti, Gilberto Zorio, and Giuseppe Penone, as well as international artists including Sol LeWitt, Robert Barry, and Joseph Kosuth. During this period, he began exhibiting his work in both solo and group shows, focusing on photography and language-based pieces, such as marble tombstone inscriptions. In 1973, he shifted exclusively to painting, initially focusing on mythological subjects and reinterpretations of works by Raphael, Carpaccio, and other masters. From the 1980s onward, his work explored still lifes, cityscapes, and landscapes—both Mediterranean and from around the world—marked by an ongoing investigation into light and color, a pursuit that continued until his death in 2015. Salvo’s work has been presented in numerous solo exhibitions at institutions including the Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin (2024); MACRO, Rome (2021); Museo d’Arte della Svizzera Italiana, Lugano (2017); Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin (2007); Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Bergamo (2002); Villa delle Rose, Bologna (1998); Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, and Musée d’Art Contemporain, Nîmes (1988); Kunstmuseum, Lucerne (1983); Museum Folkwang, Essen, and Mannheimer Kunstverein (1977).

Leonardo Sciascia (Racalmuto, 1921 – Palermo, 1989) was one of the most influential Italian writers and intellectuals of the twentieth century. He authored both fiction and essays blending civic inquiry with literary invention, including Le parrocchie di Regalpetra (1956), The Day of the Owl (1961), To Each His Own (1966), Todo modo (1974), Candido (1977), and The Moro Affair (1978). His works have been translated into many languages and inspired film adaptations by directors such as Elio Petri and Damiano Damiani. A contributor to newspapers and cultural journals, he received international recognition and served both in the European Parliament and in the Italian Chamber of Deputies as an independent leftist. His reflections on justice, power, and historical memory remain central to contemporary cultural debates.

finanziato dall'Unione Europea - Next Generation EU